4 Legal Implications Of Donald Trump’s Win

How will Trump’s return to power affect the Supreme Court, lower federal courts, the Justice Department—and the DOJ’s cases against Trump?

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking here.

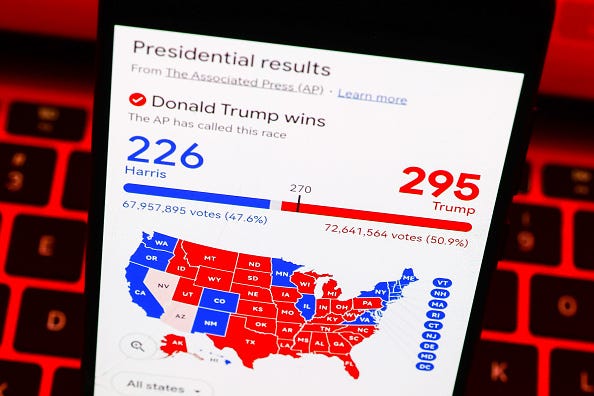

On Tuesday, November 5, former president Donald J. Trump defeated Vice President Kamala Harris in the 2024 presidential election. On Inauguration Day—January 20, 2025—Trump will be sworn in as the 47th president of the United States.

As I recently mentioned, I’m not a political commentator, nor do I aspire to become one (as my former Above the Law colleague Elie Mystal has). But if you want to talk politics, have at it. This is a Notice and Comment (N&C) post, so comments are open to all, not just paid subscribers. Lament or laud the 2024 election, as you see fit.

I’ll stick to the law stuff—specifically, implications of the Trump victory for four legal issues. Feel free to react in the comments to my thoughts as well.

1. Trump could cement—but probably not expand—the conservative supermajority on the U.S. Supreme Court.

During his first term, Trump appointed three conservative, relatively young Supreme Court justices: Justices Neil Gorsuch (57), Brett Kavanaugh (59), and Amy Coney Barrett (52). These appointments—especially those of Justice Kavanaugh, who replaced the less conservative Justice Kennedy, and Justice Barrett, who replaced the liberal Justice Ruth Ginsburg—shifted the Court significantly to the right. The resulting 6-3, conservative supermajority made possible the overruling of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

The three liberal justices—Justices Sonia Sotomayor (70), Elena Kagan (64), and Ketanji Brown Jackson (54)—would give Trump a SCOTUS seat only over their (literal) dead bodies. They’re all under the average SCOTUS retirement age, which hovers somewhere north of 75, and they all appear to be vigorous and healthy (yes, Justice Sotomayor has diabetes, but she’s had it since she was a child and manages it well). It’s highly unlikely that any Democratic SCOTUS appointee will be going anywhere between now and 2029.

In contrast, Justices Clarence Thomas (76) and Samuel Alito (74) are in the ballpark of retirement age. Ed Whelan predicted over at National Review that Justice Alito will announce his retirement in spring 2025—i.e., the end of the current Term. And that makes sense to me, for a few reasons: (1) Justice Alito has never been a fan of D.C.; (2) Martha-Ann would surely love for him to retire, for obvious reasons; and (3) he’ll never write an opinion as consequential as his majority in Dobbs.

Justice Thomas is trickier. With originalism now in control at the Court, he’s arguably more influential than he has ever been—why would he want to leave now? Since he started speaking up at oral argument a few years ago, he seems to be enjoying his job more. And there might be a part of him that likes “sticking it to the libs”—which he gets to do with every day that he’s sitting on the Court.

But he might be persuadable—especially if the Trump administration implies (or promises) that they’ll replace him with one of his former clerks who would carry on his legacy, like Judge James Ho (5th Cir.) or Judge Kathryn Mizelle (M.D. Fla.). Ed Whelan suggested that Justice Thomas might retire in 2026, which seems at least possible to me (unless Justice Thomas wants to surpass Justice William O. Douglas as the longest-serving justice, which he’d do if he serves to the end of Trump’s new term).

With Republicans holding somewhere between 52 to 54 seats in the Senate, Trump will have ample leeway in selecting a nominee. He can make an ultra-conservative pick, lose the votes of a Senator Collins or Murkowski, and still get the nominee confirmed. So if Justices Thomas and Alito retire during the first two years of Trump’s term, when he’ll have a favorable Senate, Trump would be able to replace them with successors who are just as conservative—but decades younger.

That wouldn’t necessarily make the Court more conservative; after all, it would be hard to outflank Thomas and Alito on the right. But it would dramatically increase the likelihood of the conservative supermajority enduring for another generation.

[UPDATE (11/10/2024, 8:28 a.m.): For additional discussion, see Josh Blackman, who has his doubts about a Thomas retirement anytime soon, and Ed Whelan, who argues that “it would be foolish of [Thomas] to risk repeating Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s mistake—hanging on only to die in office and be replaced by someone with a very different judicial philosophy.”]

[UPDATE (11/17/2024, 10:32 p.m.): Based on new reporting and some conversations I’ve had with knowledgeable people, I now believe that Alito and Thomas retirements are unlikely.]

2. Trump could shift the rest of the federal judiciary further to the right—but not as much as he did in his first term.

While the Supreme Court gets most of the attention, the lower courts, especially the circuit courts, are incredibly important. And during his first term, Trump left his mark, securing the confirmation of 234 nominees to Article III judgeships—including more than 50 circuit judges.

But it’s unlikely that he’ll come anywhere close to that in his second term. According to Bloomberg Law, at the end of last month, only 46 pre-election judicial vacancies remained for Trump, including some seats with pending nominees. That’s less than half of the 100-plus pre-election vacancies that Trump inherited in 2017, as a result of Republicans successfully blocking Obama nominees (and the Obama administration not even making nominations for a number of judgeships).

To be sure, new vacancies will arise during the course of Trump’s second term, with 25 circuit judges becoming eligible for retirement in 2025. But some of those 25 were appointed by Democratic presidents—and it’s increasingly the case that judges are waiting to retire until the party of their nominating president controls the White House.

So will Trump be able to move the lower courts further to the right? Sure—but it will be more of a nudge than a push, nothing as transformative as his first term.

3. The second Trump DOJ could be a lot like the first Trump DOJ—but much will depend on who goes into the administration.

If I had to guess, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) in Trump’s second term will be similar to the DOJ during his first term. There will be relatively less emphasis on white-collar crime and relatively more emphasis on violent crime, including gang activity. There will be more focus on protecting religious liberty and investigating “reverse discrimination”—e.g., looking into whether schools are complying with the Supreme Court’s affirmative-action ruling—and less focus on environmental crime and minority voting rights. It will look in many ways like a traditional Republican DOJ.

One area where the first Trump DOJ diverged from a traditional Republican DOJ was in antitrust enforcement, where Team Trump took a relatively aggressive approach—which the Biden Administration maintained, under Jonathan Kanter at the Antitrust Division and Lina Khan at the Federal Trade Commission. I could see the second Trump administration continuing down the same path, especially when it comes to scrutinizing tech companies (except ones owned or controlled by Elon Musk).

In his first term, Trump sought—and sometimes obtained—DOJ investigations of his adversaries. This might happen in his second term as well, as outlined in The New York Times, and Politico recently drew up a list of Trump enemies who could be targeted—e.g., the Bidens, the Cheneys, prosecutors who have pursued Trump over the past few years, members of the January 6 committee, and members of the media.

But it’s also possible that Trump might not seek revenge (or seek it to a more limited extent than some people are expecting). Marc Short—chief of staff to vice president Mike Pence when Pence refused Trump’s request to not certify the 2020 election results, and therefore an object of Trump’s ire—told Peter Baker of The Times that he’s not worried: “I think there’s a lot of theater around that more than there is real sort of retribution.”

Would attempts by Trump to weaponize the justice system be successful? Much will turn on who enters his administration. A list of possible Trump DOJ appointees obtained by ABC News includes people like Steve Engel, former head of the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), who joined with other top DOJ officials in January 2021 and threatened to resign if Trump named Jeffrey Clark attorney general so Clark could pursue Trump’s claims of election fraud. But that same list of potential DOJ picks also includes… Jeffrey Clark.

4. Jack Smith’s cases against Trump are not long for this world.

The extent to which the DOJ will become a personal tool of Donald J. Trump is unclear. Here’s something that is clear: Special Counsel Jack Smith’s two cases against Trump—the election-interference case that’s before Judge Tanya Chutkan (D.D.C.), and the classified-documents case that’s on appeal to the Eleventh Circuit, after being dismissed by Judge Aileen Cannon (S.D. Fla.)—are going away.

As Professor Ray Brescia of Albany Law School told me, “It seems clear that Smith is preparing to wind down his investigation and prosecution based on the longstanding Department of Justice policy of not prosecuting a sitting president. I am assuming he will step down before Inauguration.” (According to The Washington Post, Smith could still give Trump a little parting gift: a report of his findings, which could be scathing—and which Attorney General Merrick Garland would presumably make public, as he has pledged to do regarding special-counsel reports.)

So DOJ policy prohibits the prosecution of a sitting president, as noted by Professor Brescia. But does it require automatic dismissal of previously filed cases, without any action from Trump or his attorney general? Or does Trump have to “own it” politically, by taking some affirmative step to oust Jack Smith? (Not that I think Trump would have a problem with that—he’s previously said he would “fire [Smith] within two seconds” if reelected, and even if Smith should actually be dismissed by the attorney general, I could totally see Trump picking up the phone, calling Smith himself, and barking at him, Apprentice-style, “You’re fired!”)

In an October 2000 OLC memo, then-OLC head Randy Moss (now Judge Randy Moss) concluded that “a sitting President is immune from indictment as well as from further criminal process.” Moss also concurred with a 1973 OLC memo stating that “a grand jury should not be permitted to indict a sitting President, even if all subsequent proceedings were postponed until after the President left office.” But I’m unaware of any OLC memo specifically addressing the current situation, in which a former president gets indicted and then… becomes president again. (I can’t fault OLC for not exploring this issue; when he takes office in January, Trump will become only the second president, after Grover Cleveland, to serve nonconsecutive terms.)

The state prosecutions against Trump—the New York hush-money case in which Trump is scheduled to be sentenced later this month, and the Georgia election-interference case tied up in appellate proceedings because of the Fani Willis-Nathan Wade romance—are not controlled by DOJ policies. But they are, as a practical matter, going away—at least until Trump finishes his term, if not forever.

In the New York case, Trump is scheduled to be sentenced on November 26. But as legal experts told Politico, it’s unlikely that Justice Juan Merchan will proceed with sentencing a president-elect. Even a noncustodial sentence like probation would present issues—e.g., can a sitting U.S. president be required to check in with a state probation officer? But whether Justice Merchan would postpone sentencing until after Trump leaves office or get rid of the case entirely—perhaps by granting Trump’s pending motion to dismiss based on the Supreme Court’s immunity ruling—is unclear.

As for the Georgia case, many analysts agree with Steve Sadow, Trump’s lead attorney in Georgia, who previously argued that under the Supremacy Clause, state criminal prosecutions can’t move forward against Trump as long as he’s a sitting president. Whether that case would go away completely or could return in 2029 is also uncertain. But again, practically speaking, it’s going dormant—and will remain that way for years.

So those are some of my thoughts on the implications for four legal issues of Trump’s win. What are your views? Please share them in the comments of this N&C post, which are open to all readers (not just paid subscribers). I will not be opining on the political aspects of Trump’s victory—but you’re welcome to do so, and I look forward to your thoughts.

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; (3) transcripts of podcast interviews; and (4) the ability to comment on posts. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

Trump enjoys theatrical gestures - perhaps he will embrace in bipartisan fervor the Democrats' court expansion plan and enjoy the spectacle of them having to reverse themselves on expanding the Court.

My prediction: Alito will announce his retirement in July 2025, at the conclusion of the current SCOTUS term. Thomas will stay on the Court for another three years until he passes William O. Douglas as the longest serving Justice in U.S. history in June 2028. He'll announce his retirement pending the confirmation of his successor, and Trump will have time to replace him before the 2028 election (the 2026 Senate map looks terrible for Dems, so while I expect them to retake the House in the midterms, the GOP should keep their Senate majority).