Perlot v. Green: The Latest Law School Free Speech Controversy

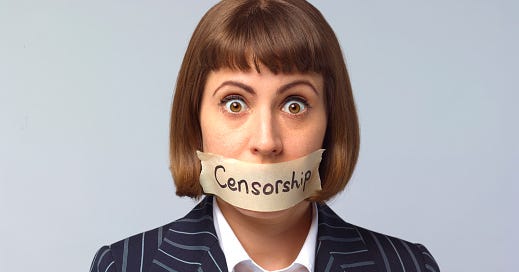

In a free society, you can't force people to approve of your actions or to agree with your views.

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking on the button below. Thanks!

On June 30, Chief Judge David Nye (D. Idaho) issued a noteworthy opinion in Perlot v. Green. It came down shortly before the July 4th holiday, so it was easy to miss, and I actually did miss it. Thanks to Eugene Volokh for writing about it, and thanks to the reader of mine who flagged Volokh’s post for me.

Here are the facts. On April 1, the University of Idaho College of Law (“University” or “Idaho Law”) held a “moment of community” in response to an anti-LGBTQ+ slur left anonymously on a classroom whiteboard. Event attendees included plaintiffs Peter Perlot, Mark Miller, and Ryan Alexander, who at the time were law students and members of the Idaho Law chapter of the Christian Legal Society (“CLS”), and Professor Richard Seamon, the CLS faculty advisor.

At the April 1 event, the plaintiffs gathered in prayer to express support for the LGBTQ+ community. After the prayer was over, Jane Doe, a queer female student at Idaho Law, approached the plaintiffs and asked them why the CLS constitution declares that marriage is between one man and one woman. Miller explained that the CLS adhered to traditional biblical views of marriage and sexuality, and he and Jane Doe then debated whether the Bible actually supports such a conclusion. Professor Seamon allegedly affirmed Miller’s explication of the CLS view on marriage.

Soon after the event, Perlot left a handwritten note on Jane Doe’s study carrel, which read in its entirety as follows: “I’m the president of CLS this semester. Feel free to come talk to me if you have anything you need to say or questions you want to ask. I'm usually in my carrel: 6-034. over by the windows. Peter [smiley face].” According to the Idaho Law officials who are the defendants in this case, Jane Doe interpreted the leaving of the note as “violating” her private carrel with “messaging she interpreted as one of the Plaintiffs’ efforts to proselytize about extreme hateful religious dogma that [she] emphatically rejects.”

On April 4, several students staged “walkouts” for two classes taught by Professor Seamon, apparently in response to the views he expressed at the April 1 event. Also on April 4, defendant Lindsay Ewan, deputy director of the law school’s Office of Civil Rights and Investigations (“OCRI”), interviewed Miller about the April 1 event.

On April 7, the University issued no-contact orders to the plaintiff students, after Jane Doe reported to OCRI that plaintiffs’ actions left her feeling “targeted and unsafe.” The orders prohibit plaintiffs from having any contact with Jane Doe without advance permission from OCRI, apply on and off campus, have no end dates, and provide that violation could lead to suspension or expulsion.

OCRI also issued a limited no-contact order against Professor Seamon, after he emailed Jane Doe, a student in one of his classes, and expressed concern for her well-being in the wake of the heated discussion at the April 1 event. The order prohibited Seamon from contacting Jane Doe for anything except “what is required for classroom assignment, discussion, and attendance.”

Represented by the Alliance Defending Freedom—which describes itself as “an alliance-building, non-profit legal organization committed to protecting religious freedom,” but which its critics attack as an anti-LGBTQ+ “hate group”—the plaintiffs sued. Seeking a preliminary injunction, the plaintiffs requested that the defendants rescind the no-contact orders and stop enforcing policies that restrict or punish “pure speech… that does not rise to the level of harassment.”

After briefing and oral argument, Chief Judge Nye granted the requested relief, reasoning as follows:

Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on their claim that defendants violated their First Amendment right to free speech by issuing the no-contact orders.

By issuing no-contact orders against the plaintiffs after they expressed their sincerely held religious beliefs about marriage, while not taking any action against community members who expressed opposing beliefs about the same subject, the University engaged in content-based regulation of speech.

Such regulation must survive strict scrutiny, which it can’t in this case. Defendants justify the no-contact orders based on Title IX, which prohibits harassment “on the basis of sex.” Although Jane Doe seems to believe the plaintiffs engaged in “sexual harassment” because of her sexual orientation, no reasonable person would find “harassment” here.

Title IX prohibits harassment “determined by a reasonable person to be so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively denies a person equal access to the University’s education program”; it does not create a general right to be free from being bothered. The law draws a clear distinction between speech attempting to persuade others to change their views and intrusive, offensive speech that the unwilling audience cannot avoid. The former is protected, even if the message might be offensive to some.

A person’s interest in freedom from “importunity, following, and dogging” ripens only after an offer to communicate has been declined. Here, Jane Doe never declined to speak with plaintiffs, never asked them to stop talking to her, and even initiated some of the interactions, like the April 1 discussion.

Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on their claim that defendants violated their First Amendment right to free exercise of their religion because they were punished for exercising their rights to profess their religious views and share them with others. Plaintiffs are also likely to succeed on their due-process claim because defendants issued the no-contact orders with hardly any process, nor did the defendants attempt any informal resolution before imposing the orders.

This straightforward legal analysis doesn’t require additional explanation, but I’ll just add two observations of my own.

First, getting insulted or criticized isn’t the same as being the victim of “violence.” Consider the introduction to Chief Judge Nye’s opinion:

This case present questions of immense import to all Americans. It involves the clash of two groups’ constitutional rights. The Freedom of Speech and the Freedom of Religion are enshrined in the Constitution. So too, is the right to Equal Protection and to be free from unlawful discrimination and harassment. Much can be said about the intersection, and overlapping nature, of these rights and the degree to which one right impacts another. An oft-quoted statement—attributed to various Supreme Court Justice and legal scholars—explains that the “right to swing your arms ends just where the other man’s nose begins.”

This saying underscores the proper definition of “violence,” which is still the first definition in the dictionary: “the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy” (emphasis added).

If you punch someone in the nose, the law can address that through civil liability or criminal punishment. If you say someone has an ugly nose, that might be rude—but it’s not “violence,” and your comment is constitutionally protected opinion.

As an Asian American, a gay man, and someone who has written on the internet for almost two decades, I have lost count of the slurs, insults, and other negative things that have been said to or about me over the years. When I first started blogging, an insult would get under my skin, and I’d dwell on it for days. Today—after years of putting up with this, and getting older and wiser—I often can’t remember the insults the next day. When someone says something racist or homophobic to me on Twitter, I ignore and mute them (but don’t block, not wanting to give them the satisfaction).

If you think it’s productive, you can use your own First Amendment rights to fight back. For example, in this case there’s an (unsupported) allegation that a plaintiff or plaintiffs said that homosexuality is a sin, and sinners will “swing from the gallows of hell.” Jane Doe could have responded by saying that, in her view, the plaintiffs will “swing from the gallows of hell,” based on their intolerance and bigotry.

Second, the Constitution protects the rights to believe that marriage is between one man and woman and to express that belief. As a man married to another man, I disagree with that belief, but I recognize the right of people to hold and express it.

The law does limit certain people’s ability to act on that belief in certain ways. If you’re an official who issues marriage licenses, you can’t deny a civil marriage license to a gay couple, under Obergefell v. Hodges. But religious marriage is different, as Justice Anthony M. Kennedy explained in his opinion for the Court in Obergefell:

Many who deem same-sex marriage to be wrong reach that conclusion based on decent and honorable religious or philosophical premises, and neither they nor their beliefs are disparaged here….

[I]t must be emphasized that religions, and those who adhere to religious doctrines, may continue to advocate with utmost, sincere conviction that, by divine precepts, same-sex marriage should not be condoned. The First Amendment ensures that religious organizations and persons are given proper protection as they seek to teach the principles that are so fulfilling and so central to their lives and faiths, and to their own deep aspirations to continue the family structure they have long revered.

By the same token, the First Amendment protects the right of people to criticize religious beliefs at odds with marriage equality, to label the holders of these beliefs as bigots, and to engage in concerted private action to express condemnation of their views—e.g., to sign petitions or to organize boycotts.

But government institutions, including public universities like the University of Idaho, are more constrained. When it comes to pure speech, especially speech driven by religious belief, they must be scrupulously viewpoint- or content-neutral; they can’t take sides in the culture wars. I realize these observations are painfully banal. But based on what’s happening at law schools across the country—even in Idaho, not exactly a hub of wokeness—maybe they bear repeating.

Here’s the bottom line: not everyone will like or respect you, your thoughts, or your conduct. And not everyone has to; that’s part of living in a free society. By the same token, you’re free to criticize these people, their thoughts, and their conduct. That’s part of living in a free society too.

Belated wishes for a happy Fourth of July.

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; and (3) the ability to comment on posts. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments about Original Jurisdiction, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

I'm struck - if sadly not surprised - by the extreme reaction of the student which precipitated the school's disciplinary orders. She's in for a rude awakening in the actual practice of law: as the saying goes, it ain't beanbag. She might consider a transfer to Yale.

I graduated from the U of Idaho College of Law. Judge Nye is by Idaho standards far from an extreme conservative. Professor Seaman never struck me as anything but a concerned professor. I don’t know the students involved but I’m guessing they are all relatively young and enthusiastic but clumsy vocalists about their “rights”. Judge Nye’s decision strikes me as extremely reasonable. I’m not sure what the law school was thinking but it strikes me as an overreaction.