The Roberts Court Is Roberts’s Court

Through his vote, his pen, and his leadership behind the scenes, Chief Justice Roberts exerts considerable influence over SCOTUS.

A version of this essay originally appeared in The Boston Globe, but my contributor’s agreement with The Globe allows me to republish it here. The footnotes contain material that did not appear in the Globe version of the piece, which you can think of as bonus content for Original Jurisdiction subscribers.

Over the past few years—and the past few months, weeks, and days—the Supreme Court has reminded us of its power. As the nine justices resolve major issues of national importance, from abortion to gun rights to all things Trump, they have attracted increasing scrutiny—and understandably so.

Much ink has been spilled over individual justices. We have read at great length about Justice Clarence Thomas’s vacations and Justice Samuel Alito’s flags (or, to be more precise, his wife’s flags). On a more substantive level, commentators have focused on the Court’s two newest members, Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Ketanji Brown Jackson, who have demonstrated their independence from the conservative and liberal wings, respectively.1

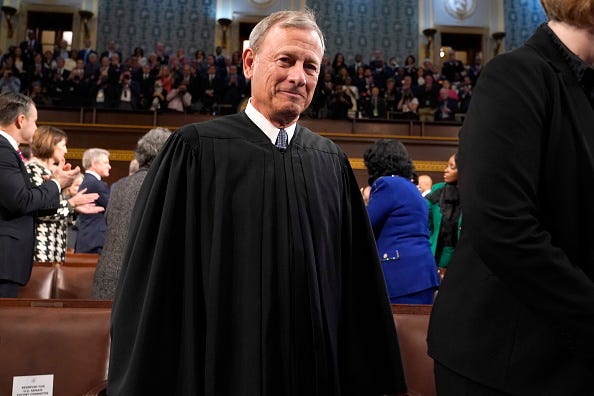

Relatively little attention has been paid to the “first among equals,”2 Chief Justice John Roberts—and one can understand why. The unassuming Roberts makes few public appearances, rarely speaks to the press, stays out of ethical trouble,3 and doesn’t write books. One of the least publicity-seeking justices since David Souter, Roberts prefers to speak through his work.4

And when you look at that body of work—whether you admire it, abhor it, or something in between—his power and influence become clear. This is John Roberts’s Court, and the other justices are just sitting on it.5

First, Roberts is important simply because of his vote. In the Term that just ended, he was the justice most frequently in the majority: according to Adam Feldman of Empirical SCOTUS, Roberts was on the winning side a staggering 96 percent of the time.6 For the two Terms prior to that, Roberts was in the majority an average of 95 percent of the time, second in 2022 only to Justice Brett Kavanaugh. In contrast, the two justices who were in the majority the least this past Term, Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, were in the majority only 71 percent of the time.

To be sure, Roberts might not be as powerful as he was four years ago. Before Barrett replaced the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2020, creating a six-justice conservative bloc that could lose a vote and still prevail, Roberts was both chief and swing justice. But even if he’s no longer the swing justice, he remains a swing justice. As noted by SCOTUS watcher Sarah Isgur, today’s Court is a “3-3-3″ Court, consisting of three liberals, three staunch conservatives, and three justices—Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett—who control the outcomes in divided cases.7

Second, Roberts has issued some of the Court’s most consequential opinions. This shouldn’t be surprising: as the most senior justice, he assigns the opinion when he’s in the majority (which, as noted, is almost always the case). And there are certain opinions, especially ones reviewing major executive actions, that are expected to come from a chief justice. One of the most famous examples is the 2012 opinion upholding the Affordable Care Act, written by—you guessed it—Roberts.

Consider Roberts’s opinions from just the most recent Term. He wrote Trump v. United States, which will go down in history as one of the most important precedents on presidential power; Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, which overruled the 40-year-old Chevron doctrine and could dramatically curtail the power of administrative agencies; Fischer v. United States, which narrowly interpreted an obstruction-of-justice law, possibly benefiting hundreds of Jan. 6, 2021, defendants (including Donald Trump); and United States v. Rahimi, which cabined the Court’s 2022 ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, hopefully keeping guns out of the hands of dangerous people.

And that’s only the latest Term. Over the past five Terms, Roberts has authored opinions like Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, which ruled against racial preferences in college admissions; Biden v. Nebraska, which held unlawful the Biden administration’s student loan forgiveness program; West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, which rejected the EPA’s Clean Power Plan, based on an increasingly important legal theory called the “major questions doctrine”; and Allen v. Milligan and Moore v. Harper, two critically important cases about election law.

Third, and finally, Roberts exerts influence through his leadership of the Court. I realize some progressives are laughing right now, given their narrative that Roberts has lost control of the Court to right-wing ideologues, but let me explain.

Despite his grandiose title of “chief justice,” Roberts is not the leader of the Court in the way that a chief executive officer is the leader of a company. Unlike a CEO, he can’t fire his colleagues or tell them what to do. Yes, he assigns opinions when in the majority, presides over courtroom proceedings, and speaks first at the justices’ private conferences. But other than these and similar responsibilities (and a slightly higher salary), he’s just like his other colleagues, one vote out of nine.

Of course, the Chief Justice can try to persuade or pressure his colleagues to vote in certain ways, especially in high-profile cases. And while we don’t know what happened behind the scenes at One First Street this past Term, some facts suggest he has been doing just that—successfully.

In the 2023-2024 Term, 46 percent of cases were decided unanimously—a significant increase from the 35 percent average of the preceding five Terms. One of those cases was Trump v. Anderson, concerning Trump’s eligibility to appear on the Republican primary ballot in Colorado—a highly contentious, politically charged case, where it benefited the reputation of the Court to present a united front. It wouldn’t be surprising if Roberts—trying to improve the Court’s weak (but improving) approval rating, during extremely polarized times—made extra efforts during this past Term to forge compromise.

What about the complaint that Roberts failed to police the ethics of his colleagues? Again, remember: he’s not the boss of them, and other than attempts at persuasion, he lacks any tools for regulating their behavior. His duties as chief justice do not include telling associate justices where to vacation or what flags they—or their wives—can fly.

In light of his limited power over his colleagues, Roberts deserves credit for the Court’s issuance last November of a written Code of Ethics—the first such code in the 235-year history of the Court. It would have been easy for the justices to do nothing, allowing the storm of bad publicity to blow over. The fact that they did issue a code—which required unanimity from nine people who clearly hold different views on their ethical obligations—was itself an achievement. Even if it lacks enforcement provisions, the Code establishes standards against which the media and the public can evaluate the justices’ conduct.8

It’s customary to refer to periods in Supreme Court history based on the chief justice, such as the Warren Court or the Rehnquist Court—but this doesn’t mean the chief justice controlled the direction of that court. For many years of the Rehnquist and Roberts Courts, two swing justices, Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy, called the shots, at least in the most controversial cases.

For better or worse, those days are gone. Make no mistake: the Roberts Court is Roberts’s Court.

Justice Barrett in particular has been the subject of a veritable cottage industry of coverage. See, e.g., Adam Liptak for The New York Times, Stephen Vladeck for The New York Times, Ann Marimow for The Washington Post, David Savage for The Los Angeles Times, Alex Swoyer for The Washington Times, Andrew Chung for Reuters, Kimberly Robinson for Bloomberg Law, and Lawrence Hurley for NBC News. (Thanks to Howard Bashman of How Appealing for most of these links.)

Original Jurisdiction readers, you heard it here first: before all of these articles were published, I observed that Justice Barrett is “parting ways with fellow conservatives when she disagrees.”

Language nerds might enjoy this Wikipedia entry on “primus inter pares,” the Latin phrase meaning “first among equals.” It notes that this expression has been used to refer to such figures as “the chair of the Federal Reserve in the United States, the prime minister in parliamentary systems, the president of the Swiss Confederation, the chief justice of the United States, the chief justice of the Philippines, the archbishop of Canterbury of the Anglican Communion, and the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople of the Eastern Orthodox Church.”

One Globe commenter complained that I didn’t mention that Chief Justice Roberts’s wife “makes millions taking bribes from attorneys who in all probability will have business before the Court.” Umm, no.

As someone who worked as a legal recruiter for two years, I’m well aware that Jane Sullivan Roberts, managing partner of the D.C. office of Macrae, is “[o]ne of Washington’s most insightful and experienced legal recruiters.” I’m unaware of any ethical violations by Chief Justice Roberts associated with his wife’s career. As Mrs. Roberts previously stated, she intentionally does not work with lawyers who have ongoing business before the Court.

Here’s what Gabe Roth of Fix the Court, nobody’s idea of an ethics dove, said about Mrs. Roberts in our podcast conversation: “She’s brilliant. She’s wealthy. She quit her job [at a law firm] and is still brilliant and is still wealthy. She was a partner, and now she’s a recruiter. It’s a total job switch. Good for her.”

Yes, I know: there’s an argument that Chief Justice Roberts, in his financial disclosures, should have referred to his wife’s recruiting income as “commissions” rather than “salary.” But I don’t believe this to be a violation. Here’s why.

Like many successful recruiters, Mrs. Roberts receives what’s called a “draw”—a regular and fixed payment, which is then offset against her future commissions. This is helpful to recruiters because it evens out what would otherwise be “lumpy” income. A draw qualifies as a “salary,” which is defined as “fixed compensation paid regularly for services.” So I don’t believe referring to Mrs. Roberts’s income as “salary” is an ethical violation.

But to remove any doubt, Chief Justice Roberts currently refers to Mrs. Roberts’s income as “recoverable base salary”—i.e., a draw—”and commission.” As his financial disclosure for calendar year 2022 explains, this new language “clarified” the nature of his spouse’s income “over prior year reports.”

I like the title of this Fix the Court post: “John Roberts Accepts No Large Gifts, Writes No Books, and Has No Billionaire Buddies (That We Know Of).”

I included this language about the Chief’s jurisprudence—”whether you admire it, abhor it, or something in between”—to make clear that I’m not taking a normative stance in this piece on his rulings, including his controversial opinion in the Trump immunity case. I’ll have more to say about that in the next edition of Judicial Notice. (As I previously mentioned I would, I took off last weekend for the Fourth of July holiday.)

It’s actually 96.61 percent, to be exact—so 97 percent if you round up.

Yes, I realize that some on the left vigorously resist the “3-3-3” characterization. They want to emphasize that the six Republican appointees are all very conservative, and the differences between the Roberts/Kavanaugh/Barrett wing and the Thomas/Alito/Gorsuch wing are trivial. Fair enough.

But it’s not just right-of-center analysts like Isgur who subscribe to the “3-3-3” theory. Last night, I watched “The Supreme Court’s Year in Review,” co-presented by the Forum on Life, Culture & Society (FOLCS) and the 92nd Street Y. Dean Bill Treanor of Georgetown Law—who’s not a conservative, and who had plenty of criticism for the some of the Roberts Court’s latest rulings—said this about SCOTUS: “The Court has three wings: three liberals, three conservatives, and three ‘real conservatives’” (to laughter).

For additional views of mine on the SCOTUS ethics code, see Originalist Perspectives on Ethics and the Supreme Court, a Federalist Society panel where I took the “liberal” position of arguing in favor of a code. My fellow panelists, all to my right, opposed adopting a Code, essentially arguing that it would constitute caving to a bad-faith campaign by the left to weaponize ethics concerns against conservative justices whose rulings they oppose. (The justices ultimately saw it my way; the panel took place on November 9, 2023, and four days later, the Court announced its Code of Conduct.)

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; (3) transcripts of podcast interviews; and (4) the ability to comment on posts. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

I tend to agree with the conclusion but I'm a bit skeptical of the methodology that presumes it's the chief justice doing the work to generate consensus.

I could easily imagine a court where some justice besides the chief functioned as a consensus maker and was responsible for convincing justices to agree on things like ethics rules (maybe merely via agreeableness not power).

My sense is also that in this court it really is Roberts who fills this role but I think that reflects a sense of the personalities.

A question about the element in the majority opinion that Barrett took exception to in her concurrence. A number of writers feel what Roberts wrote came out of left field, so to speak. I heard a podcaster say Alito mentioned it in a question at oral arguments, but that was it.

So why did Roberts add it in the opinion?

I wondered if he added it to hold another justice’s vote.

Anyone else have a guess?