When It Comes to Donald Trump, The Supreme Court Has One Job

Here are my thoughts—predictive, not normative—on whether SCOTUS will disqualify Trump from future office under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking here. Thanks!

A version of this article originally appeared on Bloomberg Law, part of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc. (800-372-1033), and is reproduced here with permission.

How do you solve a problem like disqualification? And make no mistake: The effort to disqualify Donald Trump from holding the presidency once again is a problem—for the U.S. Supreme Court.

Whether Trump should be disqualified under Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment, which bars certain former officeholders from returning to office if they have “engaged in insurrection or rebellion,” isn’t something the Court wants to decide. No matter what it does, its decision will anger millions of Americans—and threaten its plummeting public approval rating, which despite a recent uptick is still underwater (44 percent approval, 55 percent disapproval).

Alas, the American people expect the Supreme Court to offer the final word on national legal questions of this importance. So, just as they did in 2000 in Bush v. Gore, the justices will have to put on their big-kid robes and decide the case, even if it causes their popularity to take a hit (which happened after Bush v. Gore).

They will most likely tackle the controversy by hearing Anderson v. Griswold, the Colorado Supreme Court’s December 19 ruling holding that Trump is disqualified under the Fourteenth Amendment. It’s already before the SCOTUS, thanks to a certiorari petition filed by the Colorado Republican Party in Colorado Republican State Central Committee v. Anderson.

How should Anderson be decided as a matter of constitutional law? Thousands of pages of judicial opinions and legal scholarship have tackled this question, including many thorny sub-questions, and eminent jurists and legal scholars disagree. It’s a question far above my pay grade as Unfrozen Caveman Legal Pundit.

So I instead offer predictions about how the Court will handle Anderson, which the justices will almost certainly hear—because they can’t afford not to hear it.

The decision will be based on what University of Texas law professor Stephen Vladeck calls “constitutional politics,” which is distinct from constitutional law. Constitutional law isn’t irrelevant to constitutional politics, but it’s also not controlling; constitutional politics reflects additional factors like practical consequences, prudential judgments, the reputation and legitimacy of the Supreme Court, and what the justices are willing to spend in terms of political capital.

Now, my predictions. These are nothing more than predictions, and quite possibly wrong.

First, the Court is likely to keep Trump on the ballot—based on consequentialist concerns, and regardless of the legal merits. Some 74 million Americans voted for Trump in 2020. How will millions of them react to being told they can’t vote for him again?

As Yale law professor Samuel Moyn puts it, “it is not obvious how many would accept a Supreme Court decision that erased Trump’s name from every ballot in the land,” and “rejecting Trump’s candidacy could well invite a repeat of the kind of violence that led to the prohibition on insurrectionists in public life in the first place.” The backlash against the justices from such a ruling is hard to imagine.

To be sure, the current Court has ignored practical consequences and public blowback before—most famously in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overruled Roe v. Wade. But Dobbs involved constitutional principles the conservative legal movement has cared about for decades; the same isn’t true of Anderson, arising from an obscure constitutional provision that many Americans (or even lawyers) hadn’t heard of until now.

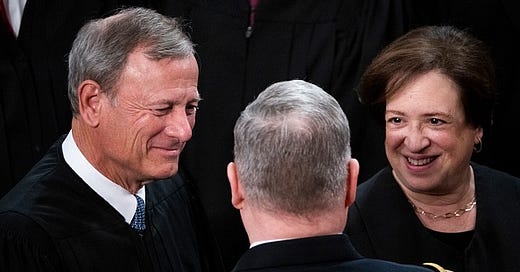

Second, I predict the vote won’t be the 6-3, conservative-liberal split that characterizes the Court’s most controversial cases. Chief Justice John Roberts will struggle mightily to cobble together a coalition that includes at least one Democratic appointee—and at least one, Justice Elena Kagan, should be sympathetic to that goal.

Both Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kagan are institutionalists who care deeply about the reputation of the Court. Both recognize the damage it would suffer if the outcome in this case is perceived as the product of partisan politics. And given the stakes, it’s conceivable that Justices Sonia Sotomayor or Ketanji Brown Jackson might join the majority as well.

Third, I suspect the Court will ultimately offer multiple rationales for keeping Trump on the ballot. Why? For starters, there actually are numerous ways to reject the attempt to disqualify Trump, reflected in the welter of lower-court decisions in his favor. The arguments against disqualifying Trump include, but aren’t limited to, the following: Section Three doesn’t apply to the presidency, which is what the trial judge in the Colorado case concluded; Section Three isn’t “self-executing,” i.e., Congress must pass enforcement legislation (which it hasn’t); Trump never “engaged in insurrection or rebellion,” as required by Section Three; the challengers of Trump’s eligibility lack standing to sue; and the case presents a “political question” that can’t be decided by courts.

But there’s another reason I expect the Court will take a “choose your own adventure” approach to Anderson. As Yale law professor Akhil Amar explained on his podcast, the 50 states have 50 different legal regimes to govern the procedure and substance of federal elections. A narrow ruling in Anderson, based on a single ground, might resolve the issue of Trump’s eligibility in Colorado—but depending on the opinion’s wording and reasoning, the decision might not control a different state with different laws.

To reduce the likelihood of the issue going unresolved in another state—and coming back to the Supreme Court later, even closer to the election—the justices will likely take a “belt and suspenders” approach in Anderson, offering up a raft of reasons for keeping Trump on the ballot. If they rely on just a single argument, they run the risk of not reaching a final, nationwide resolution of a critically important, time-sensitive issue.

And with efforts to disqualify Trump underway in multiple states—including Maine, where Secretary of State Shenna Bellows disqualified Trump on December 28, and Oregon, whose state high court is now considering the issue—the risk of the issue returning is real. Trump has sued over Maine’s ruling barring him from the primary ballot, and he is expected to appeal Colorado’s. [UPDATE (6:28 p.m.): Here is Trump’s cert petition in Trump v. Anderson.] [UPDATE (1/5/2024, 5:15 p.m.): And here is the Supreme Court’s order granting cert in Trump v. Anderson, with oral argument set for Thursday, February 8.]

So look for Chief Justice Roberts to try for a unified Court speaking through one opinion, providing many reasons for not disqualifying Trump. A second-best outcome from the Chief’s perspective would be multiple opinions offering multiple rationales, in which shifting coalitions of justices form separate majorities for discrete propositions—suboptimal, but something he can probably live with, as long as he can get seven or more justices to keep Trump on the ballot.

When it comes to Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court has one job: to expeditiously resolve, for the entire nation and with finality, whether Trump can serve again as president. No matter what the justices decide, they should reach a swift, conclusive, universally binding decision—because the fate of our democracy hangs in the balance.

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; and (3) the ability to comment on posts. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

I think you're right, David, but as a lawyer I can't help but notice that the default opinion of many (not you, necessarily, but many) seems to be as follows:

Yes, it looks like the 14th Amendment, read properly, disqualifies Trump from being elected president. Legislative history shows members of Congress discussing the fact that it applies to the presidency. Arguments about the difference between the oath taken by the president and by Congressional members and executive officers are plainly silly, as the wording of the Article II oath covers supporting the Constitution. Section 3 is obviously self-executing as much as section 1 is, and the fact that it provides a way for Congress to "remove" a disability means the disability is there until removed. Trump engaged in insurrection, as the historical interpretations cover incitement as engagement. And it's not a political question. But . . .

But it can't be enforced, obviously, no matter what the law actually says, because that would make people Big Mad. And make the Court look bad. And so it's important not only Section 3 not be enforced, but that the idea of its enforcement be resoundingly rejected in a manner that appears non-partisan.

(I am not attributing this position to you because you did not really express a view on the merits. But many have.)

I just think that's a weird position: that yes, the law is clear, but it can't be enforced because, well, of course it can't! And yet a lot of smart people on both sides say this. Enough that I think it is fair to call it the default position of smart lawyers.

And so we know that the Court will twist themselves (and the law) into pretzels to do the "adult" thing that preserves their perceived institutional legitimacy and keeps people from being Big Mad and maybe rioting or worse. And if that means pretending the law is something other than it is, well, we all have to be adults!

I dissent. I think the law here is clear and should be applied, and the public reaction and the institutional concerns about the Court's legitimacy be damned.

I know my view will never win the day. But it should.

Even as I think you are probably right about how all of this happens, and maybe keeping Trump on the ballot is simply the right thing to do, all of the "what about his voters" and "what about democracy" talk frustrates me.

Why? Because in 2000, the people spoke and they wanted Al Gore. In 2016, the people spoke and they wanted Hillary Clinton. And the Gore and Clinton voters received no special consideration when the election victory was given to their opponents.

Of course, it is not that simple. We have a system of rules (Constitution and laws) governing our elections, and according to the rules, GWB and Trump won, not the peoples' preferred candidate. And we are a nation of rules, laws, and a constitution. Sometimes the expresssed preferences of the people must give way to the rules of the system. It's fair.

Or, rather, it's fair unless the rules of the system disadvantage the Republican. Then, and only then, can we elevate concerns of democracy over our rules-based constitutional order. It is a double standard.