Yale Law Is No Longer #1—For Free-Speech Debacles

Congratulations, Stanford Law, you're now in the limelight.

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking on the button below. Thanks!

Congratulations, Stanford Law School. You’re the nation’s new top law school—when it comes to free-speech debacles.1 (And I’m interrupting my vacation to cover you—so thanks for that too, SLS.)

As I first learned via this detailed Twitter thread and subsequent Bench Memos post by Ed Whelan, yesterday Judge Kyle Duncan of the Fifth Circuit was the subject of a highly disruptive protest when he spoke at Stanford Law School. I have received extensive information about the event from multiple sources at or affiliated with SLS, as well as Judge Duncan himself, whom I interviewed by phone, and I’ll share it with you now. I also reached out to Stanford Law, but have not yet heard back; I will update this story (or write a new one) if and when I do. [UPDATE (3/12/2023, 4:30 p.m.): Please note the multiple UPDATES at the end of this post, which reflect the responses of both Stanford Law and Stanford University to the events described in this story.]

On Thursday, March 9, Judge Kyle Duncan (5th Cir.) was invited to speak at Stanford Law by the Stanford Federalist Society. The title of his talk, scheduled to run from 12:45 to 2:00 p.m., was The Fifth Circuit in Conversation with the Supreme Court: Covid, Guns, and Twitter. Whether or not you agree with the rulings of the very conservative Fifth Circuit—and, for the record, I disagree with many of them—the opportunity to hear from a sitting federal appellate judge about his court’s jurisprudence is why students go to places like SLS.

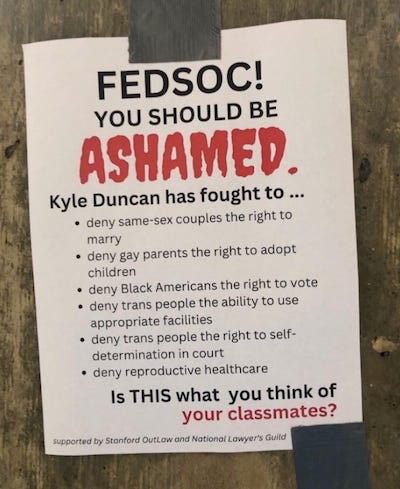

But many students at Stanford Law, especially those on the progressive side of the aisle, disagree. They have major problems with Judge Duncan, in terms of both his work as a lawyer before taking the bench and his rulings since President Donald Trump appointed him to the Fifth Circuit in 2018. Ahead of his appearance, they put up posters around the law school like this one, accusing him of being transphobic, homophobic, and racist:

Are the accusations against Judge Duncan justified? Read his judicial opinions—not descriptions of them from interested parties, but the actual opinions—and decide if this poster accurately characterizes them. I have read a number of them when preparing my weekly Judicial Notice news roundups, and I dislike the outcomes of several them as a policy matter. I also disagree, as a policy matter, with many of the positions he advanced as a litigator before becoming the bench—not surprising, since I’m in a same-sex marriage, and my husband and I are raising a son together. But there’s an important, often overlooked distinction between policy and law.

A different poster included headshots of Fed Soc board members, along with their names and class years, and the title, “Meet the Federalist Society's 2022-2023 Board. You Should Be Ashamed.” I’m not a fan of posters like this; as one of my sources put it, they amount to “intimidating and ostracizing students just for their membership in an organization.” As I have repeatedly emphasized, I prefer environments were people can disagree with each other, even vehemently, without engaging in call-out culture.

But I wouldn’t ban posters criticizing Judge Duncan or Stanford FedSoc, provided that the posters otherwise comply with university policy (e.g., by not covering up fliers promoting the event, as we saw in the recent controversy at Northwestern Law). Members of Stanford FedSoc are entitled to invite Judge Duncan to campus, but they are not entitled to have him be well-received or to have their decision to invite him go unquestioned (or to be protected against mockery in satirical fliers). Liberal and progressive students have their own free-speech rights, which they are free to exercise as long as they don’t prevent others from speaking or otherwise violate university policy. And while there are policies against harassment and the like, I don’t consider the “Meet the FedSoc Board” poster to rise to the level of “harassment.”

The posters gave the Stanford Law community, including the SLS administration, a warning that trouble might lie ahead. So yesterday morning, Tirien Steinbach, Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, sent an email to all Stanford Law students stating that the Law School would be taking no action to prevent the event, despite the fact that “[f]or some members of our community, Judge Duncan, during his time as an attorney and judge, has ‘repeatedly and proudly threatened healthcare and basic rights for marginalized communities, including LGBTQ+ people, Native Americans, immigrants, prisoners, Black voters, and women, and his presence on campus represents a significant hit to their sense of belonging.’” She continued that students were free to protest, in compliance the school's policy against disrupting speakers. (I have posted the full text of Dean Steinbach’s email below.)

Later on Thursday morning, after wrapping up classes, some members of Stanford FedSoc and their friends went into the student lounge, Russo Commons, to eat breakfast (since it was raining, and the lounge is one of the few indoor areas where food is allowed). Unbeknownst to them, that was the area where the protestors were preparing for the Duncan event. Someone came up to them and told them to leave because the protestors were trying to create a “safe space” for the LGBT community, meaning that FedSoc members were not welcome—so they left.

Leading up to the event, Russo Commons took on a festive air. Stanford’s OutLaw and National Lawyers Guild chapters served Mexican food to protesters, some of whom had their faces painted. Colorful signs were everywhere. A dog decorated with a transgender flag was running around. It felt like an eagerly anticipated social occasion, one FedSoc member told me.

Then the event got underway. Approximately 100 protesters lined up outside the event to boo those who entered, with some students calling out individual classmates—e.g., “Shame, John Smith”—à la Cersei’s Walk of Atonement on Game of Thrones. Another 50 to 70 students came into the room where the event took place, compared to about 20 FedSoc students (if that). The protesters carried signs reading "RESPECT TRANS RIGHTS," "FEDSUCK," "BE PRONOUN NOT PRO-BIGOT," and "JUDGE DUNCAN CAN'T FIND THE CLIT" (among others), along with trans-rights flags.

I have no problem with quietly holding up signs (as long as the signs, consistent with many universities’ policies, don’t prevent attendees from seeing the speaker if they wish to). I also have no problem with protesters outside or even inside the room where an event is taking place, as long as they are quiet and not disruptive.

But here’s where things went off the rails. When the Stanford FedSoc president (an openly gay man) opened the proceedings, he was jeered between sentences. Judge Duncan then took the stage—and from the beginning of his speech, the protestors booed and heckled continually. For about ten minutes, the judge tried to give his planned remarks, but the protestors simply yelled over him, with exclamations like "You couldn't get into Stanford!" "You're not welcome here, we hate you!" "Why do you hate black people?!" "Leave and never come back!" "We hate FedSoc students, f**k them, they don't belong here either!" and "We do not respect you and you have no right to speak here! This is our jurisdiction!"

Throughout this heckling, Associate Dean Steinbach and the University's student-relations representative—who were in attendance throughout the event, along with a few other administrators (five in total, per Ed Whelan)—did nothing. FedSoc members had discussed possible disruption with the student-relations rep before the event, and he said he would issue warnings to those who yelled at the speaker, but only if the yelling disrupted the flow of the event. Despite the difficulty that Judge Duncan was having in giving his remarks, plus the fact that many students were struggling to hear him, no action was taken.

After around ten minutes of trying to give his remarks, Judge Duncan became angry, departed from his prepared remarks, and laced into the hecklers. He called the students “juvenile idiots” and said he couldn’t believe the “blatant disrespect” he was being shown after being invited to speak. He said that the “prisoners were now running the asylum,” which led to a loud round of boos. His pushback riled up the protesters even more.

Eventually, Judge Duncan asked for an administrator to help him restore order. At this point, Associate Dean Steinbach came up to the front and took the podium. Judge Duncan asked to speak privately between them, but she said no, she would prefer to speak to the crowd, and after a brief exchange, Dean Steinbach did speak. She said she hoped that the FedSoc chapter knew that this event was causing real pain to people in the community at SLS. She told Judge Duncan that “she was pained to have to tell him” that his work and previous words had caused real harm to people.

“And I am also pained,” she continued, “to have to say that you are welcome here in this school to speak.” She told Judge Duncan that he had not stuck with his prepared remarks and was partially to blame for the disruption for engaging with the protesters. She told Judge Duncan and FedSoc that she respected FedSoc’s right to host this event, but felt that “the juice wasn't worth the squeeze” when it came to “this kind of event.” She told the protestors that they were free to either stay or to go, and she hoped they would give Duncan the space to speak—but as one FedSoc member told me, the tone and tenor of her remarks suggested she really wanted him to self-censor and self-deport, i.e., end his talk and leave. [UPDATE (10:57 p.m.): The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) posted a transcript of Dean Steinbach’s remarks at the Judge Duncan event, if you’d like to read her words for yourself.]

“This invitation was a setup,” Judge Duncan interjected at one point while Dean Steinbach criticized him. And I can see what would give him that impression: as you can see from this nine-minute video posted by Ed Whelan, when Dean Steinbach spoke, she did so from prepared remarks—in which, as noted by Whelan, she explicitly questioned the wisdom of Stanford’s free-speech policies and said they might need to be reconsidered. (At least at Yale Law School, Dean Heather Gerken had the decency to criticize disruptive protesters, instead of validating them.)

As you can see from the video, about half of the protestors eventually left at the direction of a student protest leader, with one of them charmingly calling the judge “scum” as she walked out. Yet the heckling continued, and still the administrators did nothing to intervene. Eventually, the student-relations representative tried to intervene once it had become clear that the event was out of control—but Judge Duncan then criticized him, telling him that he should have acted sooner.

Not getting traction trying to give a speech, Judge Duncan moved on to the question-and-answer session, and the protestors quieted down enough to ask a few questions. The questions—and answers—were generally contemptuous. As the judge put it to me, while he’s usually happy to answer questions when he speaks at law schools, the questions he received at Stanford were not asked in good faith; in his words, they were of the “how many people have you killed” or “how many times did you beat your wife last week” variety.

At one point during the Q&A, Judge Duncan said, “You are all law students. You are supposed to have reasoned debate and hear the other side, not yell at those who disagree.” A protestor responded, “You don't believe that we have a right to exist, so we don't believe you have the right to our respect or to speak here!”

Finally, the event concluded when the heckling was so disruptive and Judge Duncan was so flustered that it could not continue. One source told me the event ended about 40 35 minutes before the scheduled end time (although a second source told me they thought it ran for a bit longer). So defenders of the SLS protest might argue that technically the judge wasn’t “shouted down,” since he did get to speak for some amount of time. But it was difficult for many to hear him, and it’s a pretty sad commentary on the state of free speech in American law schools if the ability to get out a few words is the standard for acceptable events. (As for why shouting down speakers is not itself a legitimate form of “free speech,” which is what a number of Stanford protesters claimed, I refer you to one of my earlier stories about Yale Law, as well as this post by Professor Eugene Volokh over at Reason.) [UPDATE (3/15/2023, 8:10 p.m.): Revised to say the event ended 35 minutes before its scheduled end time, based on having listened to a full audio recording of the proceedings—which you can listen to as well, if you want to form your own opinions.]

After the event, Stanford FedSoc members asked Dean Steinbach for her thoughts. She asserted that nothing the protestors had done violated the Stanford disruption policy and that the event had been “exactly what the freedom of speech was meant to look like—messy.” She said that if Judge Duncan had wanted to give his remarks, he should have just kept reading them, and she claimed that he was disrespectful to the attendees.

And is there a case for that? I have readers and sources on both sides of the aisle, I believe in presenting both sides of controversies, and I’ll now quote from a source who was critical of how Judge Duncan conducted himself:

While I think the administration should have handled it differently, my main takeaway is that I have never seen a grown man—let alone a federal judge—comport himself so poorly.

From the moment Judge Duncan arrived on campus, he seemed to be looking for a fight. He walked into the law school filming protestors on his phone, looking more like a YouTuber storming the Capitol, than a federal judge coming to speak.

Judge Duncan, whom I offered the opportunity to respond to these allegations, did not deny this claim: “Did I try to record video? Damn right I did. I wanted to make a record.”

Back to my source:

He was heckled pretty relentlessly, but I truly can't have imagined a worse reaction. He could have had a moral victory if he’d stayed on message, kept his cool, and delivered his prepared remarks. He even had a heads-up that the event was likely to be disrupted, so I would have thought that he would have had time to prepare himself to stay composed.

Judge Duncan told me that while he was warned about possible protest, what he encountered far exceeded his expectations, as well as anything he has ever encountered at any of the many law schools he has spoken at. He also shared with me that he had received assurances from the SLS administration—through Professor Michael McConnell, the prominent conservative legal scholar and former Tenth Circuit judge, who served as intermediary—that while there might be protesters, they would not be disruptive. So Judge Duncan was definitely (and understandably) caught off guard by what transpired yesterday.

Back to Judge Duncan’s critic:

[The judge] lost his cool almost immediately. He started heckling back and attacking student protestors…. Someone accused him of taking away voting rights from Black folks in a southern state. He asked the student to cite a case. While she was looking up the case, he berated her, “Cite a case. Cite a case. Cite a case. You can't even cite a case. You really expect this to work in court” [not exact quotes, but something along these lines]. When she eventually cited the one she was referring to, he said something along the lines of, “Was I even on that panel?” When she told him he was, he just moved right along with his tirade.

Judge Duncan said the case didn’t ring a bell for him because he couldn’t recall any opinion of his that was about disenfranchising Black voters. He told me that after the talk, he looked up the case cited by the questioner—and found he actually dissented.

I ended up leaving before the end of the event, but from what I heard, during the Q&A, one student shared that she’d been raped in college and asked a pointed question. His response was something along the lines of, “Nice story.” Someone asked him a question about this decision denying a pro se motion to use the petitioner's preferred pronouns, basically saying, "In court we are supposed to show respect for judges and co-counsel, even if you couldn't force other judges to use the litigant’s pronouns, couldn't you have shown that person some respect and addressed them how they wished to be addressed?” Duncan's response: "Read the opinion. Next question."

According to one Stanford FedSoc student, when you do read the opinion, you’ll see that it “is not some screed against trans people,” but an opinion addressing technical issues of jurisdiction and procedure.

When asked what he meant when he said that Obergefell would “upset the civil peace,” he gestured at the room of mostly queer protestors and implied that the disruption at the event proved his point.

If the students should be embarrassed by their behavior during the event, which I think they probably should be, Duncan ought to be ashamed. Law students are adults and should act accordingly. Duncan is a federal judge and should also act accordingly. He did not.

I think folks on all sides agree that it was a day to forget. Sorry for the stream of consciousness.

What did Judge Duncan have to say for himself in general? In a phone interview this afternoon, he made several points to me:

“I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me because I had to endure a bunch of people jeering at me. I did think it was outrageous and unacceptable, but nobody should feel sorry for me. I’m still going to be a judge, and I’m still going to decide my cases.”

“I do feel bad—and outraged—for the Stanford FedSoc students. They are awesome people who just want to invite interesting judges to come talk to them. They’re a small group, obviously way outnumbered. They are the ones who lack power and status at Stanford Law. It’s ridiculous that they can’t get treated with civility, and it’s grotesquely unfair.”

“I get where my critics are coming from, and I understand why they don’t like me. They claim that I am marginalizing them and not recognizing their existence. But this is hypocritical of them, since that’s exactly what they are doing to their classmates in FedSoc.”

“I get the protesters, they are socialized into thinking the right approach to a federal judge you don’t agree with is to call him a f**ker and make jokes about his sex life. Awesome. I don’t care what they think about my sex life. But it took a surreal turn when the associate dean of DEI got up to speak…. She opens up her portfolio and lo and behold, there is a printed speech. It was a setup—and the fact that the administration was in on it to a certain degree makes me mad.”

“I later heard that the associate dean of DEI was claiming two things. First, she claimed that I didn’t have a prepared speech and was just there to stir up trouble. It was a long flight out to Stanford, I’m not a professional rabble-rouser like Milo Yiannopoulos, and I’m not trying to sell a book. I actually had a speech, it was on my iPad, and I was going to be talking about controversial cases handled by the Fifth Circuit that present difficult issues because the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on them is in flux.”

“Second, she claimed that the fact that two U.S. marshals showed up at the event was a sign that I’m a rabble-rouser and disruption always happens when I speak. But I didn’t bring or invite these marshals; these marshals from the Northern District of California just showed up after getting a tip-off. I have never been protested like that at any other law school, I have known of other conservative judges who have spoken at Stanford without any problems, and I spoke there in 2019 without any problems. So I was lulled into a false sense of security.”

“You don’t invite someone to your campus to scream and hurl invective at them. Did I speak sharply to some of the students? I did. Do I feel sorry about it? I don’t.”

In hindsight, would it have been better if Judge Duncan had not lashed out at the protesters? Yes. Should he have instead acted more like Ilya Shapiro at the law school formerly known as UC Hastings (now UC Law SF), who simply made repeated unsuccessful attempts to deliver his prepared remarks? Sure. But in fairness to the judge, most people would be deeply upset by such a reception, and although Judge Duncan was aware that there would be protesters, what he encountered at SLS was far worse than what he expected. As someone who has been protested only once, by a single protester who quietly held up a sign during my talk, I’m not going to sit here and judge the judge for not acting more judicially in response to verbal abuse.

As for the protesters, they are similarly unapologetic. One SLS alum tells me that word on the street is some students want Judge Duncan to issue an apology. Added this alum, “What a debacle. They wonder why no one from our [right of center] world donates when they act like this.”

So where does Stanford Law go from here? Just as I was about to hit “publish” on this story, having worked on it most of the day (while supposedly on vacation), Dean Jenny Martinez issued the following statement to all SLS students:

Dear SLS -

Most of you have likely heard about an event on March 9, 2023 at the Stanford Law School hosted by the chapter of the Federalist Society and featuring Judge Kyle Duncan of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. A video of a small portion of the event has been circulating online.

The law school advised students who announced that they planned to protest the event of university standards and policies on freedom of speech, including the specific university policy prohibiting disruption of a public event. It is a violation of the disruption policy to “prevent the effective carrying out” of a “public event.” Heckling and other forms of interruption that prevent a speaker from making or completing a presentation are inconsistent with the policy. Consistent with our practice, protesting students are provided alternative spaces to voice their opinions freely. While students in the room may do things such as quietly hold signs or ask pointed questions during question and answer periods, they may not do so in a way that disrupts the event or prevents the speaker from delivering their remarks.

In the past few years, we have had a number of events with controversial speakers proceed without incident. Other than someone who hoped to create a meltdown for the cameras to capture, no one can be happy about what happened yesterday. In this instance, tempers flared along multiple dimensions. In such situations, an optimal outcome involves de-escalation that allows the speaker to proceed and for counter-speech to occur in an alternative location or in ways that are non-disruptive. However well-intentioned, attempts at managing the room in this instance went awry. The way this event unfolded was not aligned with our institutional commitment to freedom of speech.

The school is reviewing what transpired and will work to ensure protocols are in place so that disruptions of this nature do not occur again, and is committed to the conduct of events on terms that are consistent with the disruption policy and the principles of free speech and critical inquiry they support. Freedom of speech is a bedrock principle for the law school, the university, and a democratic society, and we can and must do better to ensure that it continues even in polarized times.

Sincerely,

Jenny Martinez

My hot take (subject to revision upon further reflection): a solid message. I appreciate Dean Martinez acknowledging that (1) “[h]eckling and other forms of interruption that prevent a speaker from making or completing a presentation are inconsistent with [university] policy”; (2) “[h]owever well-intentioned, attempts at managing the room in this instance went awry”; and (3) “[t]he way this event unfolded was not aligned with our institutional commitment to freedom of speech.” I predict she will adapt this school-wide email to respond to the powerful letter that the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression just sent to Stanford Law, expressing its deep concern over the Duncan protest.

I am very interested in seeing what Stanford Law’s “review” of the incident uncovers, whether it results in any policy changes (similar to those implemented at Yale Law), and whether Dean Steinbach faces any consequences for her attempt to manage the room that “went awry.” So stay tuned. This is my first story about Stanford Law School, but I suspect, sadly, that it won’t be my last.

UPDATES (7:39 p.m.):

Judge Duncan gave a few other interviews, including one with Aaron Sibarium of the Washington Free Beacon and one with Nate Raymond of Reuters. The judge did not mince words when speaking with Sibarium, saying that the protesters behaved like “dogs**t” and that Dean Steinbach should be fired.

So far, my SLS sources approve of Dean Martinez’s statement. Said one, “It's one of the best I've seen from her. I think it gives very ‘adult in the room’ energy to a situation where Judge Duncan, Dean Steinbach, and the protesters were not acting like adults. And it's a much better and sharper defense of free speech principles than we got from her after the FedSoc satire incident in 2021.”

Said another SLS student, “I agree with you, I think this is good. It’s heartening to see Dean Martinez speak so clearly in favor of free speech values. I’m hopeful that SLS will follow through with strong action. When it comes to free speech, words are not enough—but they are a start. We’ll be watching closely to see what comes next.”

UPDATE (3/11/2023, 12:07 a.m.): For a more critical take on Dean Martinez’s message, see this Twitter thread from Ed Whelan.

UPDATE (3/11/2023, 6:41 p.m.): A big update in this story (via Ed Whelan):

I’m pleased to break the news that Stanford president Marc Tessier-Lavigne and Stanford law school dean Jenny Martinez have issued a joint letter of apology to Judge Kyle Duncan for the violations of university policies on speech that disrupted his talk on Thursday.

The letter reads, in full, as follows:

Dear Judge Duncan,

We write to apologize for the disruption of your recent speech at Stanford Law School. As has already been communicated to our community, what happened was inconsistent with our policies on free speech, and we are very sorry about the experience you had while visiting our campus.

We are very clear with our students that, given our commitment to free expression, if there are speakers they disagree with, they are welcome to exercise their right to protest but not to disrupt the proceedings. Our disruption policy states that students are not allowed to “prevent the effective carrying out” of a “public event” whether by heckling or other forms of interruption.

In addition, staff members who should have enforced university policies failed to do so, and instead intervened in inappropriate ways that are not aligned with the university’s commitment to free speech.

We are taking steps to ensure that something like this does not happen again. Freedom of speech is a bedrock principle for the law school, the university, and a democratic society, and we can and must do better to ensure that it continues even in polarized times.

With our sincerest apologies again,

Marc Tessier-Lavigne, Ph.D.

President and Bing Presidential ProfessorJenny Martinez

Richard E. Lang Professor of Law & Dean of Stanford Law School

Judge Duncan provided the following statement to Whelan:

I appreciate receiving Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne’s and Stanford Law Dean Jenny Martinez’s written apology for the disruption of my speech at the law school. I am pleased to accept their apology.

I particularly appreciate the apology’s important acknowledgment that “staff members who should have enforced university policies failed to do so, and instead intervened in inappropriate ways that are not aligned with the university’s commitment to free speech.” Particularly given the depth of the invective directed towards me by the protestors, the administrators’ behavior was completely at odds with the law school’s mission of training future members of the bench and bar.

I hope a similar apology is tendered to the persons in the Stanford law school community most harmed by the mob action: the members of the Federalist Society who graciously invited me to campus. Such an apology would also be a useful step towards restoring the law school’s broader commitment to the many, many students at Stanford who, while not members of the Federalist Society, nonetheless welcome robust debate on campus.

Finally, the apology promises to take steps to make sure this kind of disruption does not occur again. Given the disturbing nature of what happened, clearly concrete and comprehensive steps are necessary. I look forward to learning what measures Stanford plans to take to restore a culture of intellectual freedom.

I’m glad to see the issuance and acceptance of this apology, and I also look forward to seeing what additional actions Stanford takes to address the issues raised by this episode.

UPDATE (3/12/2023, 5:29 p.m.): When going through the various points raised by his critic who emailed me, Judge Duncan omitted one item in his point-by-point rebuttal (and I failed to flag the omission for him, for which I apologize). The judge authorized me to add the following statement to this story as an update:

It’s come to my attention that I’m being criticized for my apparently insensitive response to a young woman who claimed to be a rape victim and appeared to ask about Texas’s abortion laws. I recall that being mentioned in your initial exchange with me, and evidently I didn’t respond.

As I recall, I interpreted the question essentially as a pre-planned speech about abortion, one that basically asked me to “respond” to Texas’s approach to abortion and women’s rights in general. My memory is not that I said “Nice story,” but rather that I said something like, “That’s a nice speech, but it’s not a question.” I’m not positive those were my exact words, though. I then went on to give an extended answer where I tried to explain the legal question my court was deciding in the SB8 case and the subsequent litigation in the Supreme Court, the Texas Supreme Court, and parallel litigation. Finally, I tried to explain that courts of law do not address broad questions such as “reproductive rights” or “women’s health,” but instead address specific legal questions in the context of an actual case. Such broad policy questions are for legislatures, not courts.

This won’t satisfy the critics, but that’s what I recall trying to say. Again, it was in the midst of a torrent of abuse and invective from a hostile crowd that had zero interest in giving me a fair hearing on anything.

UPDATE (3/15/2023, 10:55 a.m.): Additional updates on the Stanford Law School situation—which continues to heat up rather than cool down, unfortunately—appear in this follow-up story.

[UPDATE (3/26/2023, 11:12 a.m.): Dean Martinez sent an excellent, eloquent, 10-page memo to the SLS community about the protest and its aftermath.]

EMAIL FROM DEAN TIRIEN STEINBACH ABOUT STANFORD FEDERALIST SOCIETY EVENT WITH JUDGE KYLE DUNCAN

Today, Federal Judge Kyle Duncan (Fifth Circuit) will be speaking at an event on the topic of The Fifth Circuit in Conversation with the Supreme Court: Covid, Guns and Twitter. While Judge Duncan is not expected to present on his views, advocacy or judicial decisions related directly to LGBTQ+ civil rights, this is an area of law for which he is well known. Numerous senators, advocacy groups, think tanks, and judicial accountability groups opposed Kyle Duncan's nomination to the bench because of his legal advocacy (and public statements) regarding marriage equality, and transgender, voting, reproductive, and immigrants’ rights. However, he was confirmed in 2018. He has been invited to speak at SLS by the student chapter of the Federalist Society.

A coalition of SLS students have expressed their upset and outrage over Judge Duncan's invitation to speak at SLS. For some members of our community, Judge Duncan, during his time as an attorney and judge, has "repeatedly and proudly threatened healthcare and basic rights for marginalized communities, including LGBTQ+ people, Native Americans, immigrants, prisoners, Black voters, and women," and his presence on campus represents a significant hit to their sense of belonging.

As a member of the SLS administration, and in my role as Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, I write to share my office’s goals and roles in this situation:

To listen to community members and work to support a culture of belonging for all – where people feel that their unique contributions are recognized and respected. "Belonging" does not negate disagreement, nor discomfort - those are necessarily part of how we learn and grow as a community dedicated to teaching and training a diverse group of future lawyers and leaders. However, creating "belonging" does mean acknowledging and rectifying historic and current ways that whole groups have been excluded or marginalized within law schools and legal practice, often based on racial/ethnic identity, disability, socioeconomic status, religion, veteran status, age, and LGBTQ+ and gender identities. Creating a culture of belonging in a law school also requires exploring the many challenging ways that the law is so often an exercise in balancing “freedom to” and “freedom from,” or aligning intentions and impacts.

To support and model principles of free speech and academic freedom – SLS is committed to promoting intellectually rigorous open inquiry, aligned with the University’s statement on Academic Freedom: “Stanford University’s central functions of teaching, learning, research, and scholarship depend upon an atmosphere in which freedom of inquiry, thought, expression, publication and peaceable assembly are given the fullest protection.” Moreover, as a law school, SLS is particularly invested in upholding First Amendment principles and protections, and has a responsibility to seriously consider the danger of actions that have the potential to chill speech. And while there may be differing views on how best to address speech that is abhorrent to some or most people, one generally agreed upon way to address harmful speech is through MORE speech, rather than censoring speech (that is within the bounds of constitutionally protected speech).

Today, SLS will not censor Judge Duncan’s, nor the students’ hosting him, nor stifle free speech by canceling this engagement. This would be antithetical to our school’s principles of free speech, academic freedom, AND creating a culture of belonging. Moreover, I believe cancellation would not result in actually quieting or stopping speech or a speaker that many may find offensive or harmful, rather it would only amplify it (as we have seen played out on campuses and in media across the country). Instead, SLS supports this event going forward, and also supports the rights of students to protest this event, in keeping with University policies including those against disrupting speakers. We are also providing alternative space and programming for community members for whom their sense of belonging is undermined by this event taking place (thank you to the Levin Center for coordinating with Outlaw on alternative programming).

I do not expect all of the SLS community to agree with this approach, yet I hope that even those who disagree will better understand these decisions today, and continue to engage and advocate for greater understanding in the future. I also hope that we, as an SLS community, can continue to explore the question I posed to students at orientation: “What would it look like for SLS to create belonging WITHOUT othering?” We are not there yet, and may never be, however, to me that is still a question worth exploring in the work to advance diversity, equity and inclusion.

As some of you know, my SLS office shelves are filled with ampersands (the & symbol for "and"). When I am asked about them I tell people that, in studying and practicing law, I was trained to think and speak "either/or," however, I have found over time that the answers to many important questions are "both/and." Both/and can be uncomfortable or frustrating when seeking clarity and direction, yet, for those committed to principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion - to creating communities where all people see and feel that they belong - both/and is not only helpful, it is necessary. Today, my hope is for this community to embrace the ampersand, BOTH/AND – and practice using the skillful communication and active listening tools we will need to understand, to advocate, and to be part of creating the inclusive, diverse, just, and fair world we aspire to build.

As always, I welcome your thoughts, concerns, suggestions, and reflections.

In community -

Tirien Angela Steinbach

Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

Stanford Law School

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; and (3) the ability to comment on posts. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

Yes, I’m well aware that the First Amendment applies to governmental actors. But anyone who has read Original Jurisdiction for any significant amount of time is aware of my strong and longstanding view that we need to restore a culture of free speech and First Amendment values to educational institutions, private as well as public.

Many private universities, Stanford included, have policies in which they adopt free-speech values by, for example, prohibiting disruption of public events. And in California specifically, the Leonard Law applies certain free-speech protections to students enrolled in non-religious, private institutions of higher education in California.

A debacle indeed. Broadly speaking, this event and its aftermath provides further evidence of a disturbing and detrimental trend where viewpoints that differ from one's own are outright dismissed and ignored rather then debated. I get it, especially as a married gay man, that when it comes to those who believe things like my marriage is invalid under law, contending with such people who hold those views can be a difficult (to say the least) thing. However, contend with it I, and we, must from both a law and policy perspective. Both the hecklers and the judge in this case fed into each other's preconceived notions about each other rather than seeking to diffuse and engage in a debate. Unfortunately, all too often, the environment today rewards heckling and ignoring rather than debating, to the detriment of everyone. I have friends from across the political spectrum. I value their friendship and their perspectives even if I sometimes disagree with their positions. It is a sad state of affairs when basic decency and respect are punished instead of rewarded. This debacle, like the Yale one, should bring shame to all who fed into it. A lost opportunity.

Excellent reporting and analysis. Dean Martinez has it about right, but unfortunately neither the students nor the assigned “de-escalator” seem to have understood or been willing to follow the law school’s policies.