Affirmative Action Is Going Down

At least that's what it looks like, based on the justices' questions at oral argument.

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking on the button below. Thanks!

I’m a moderate, capable of seeing the shades of gray in almost any issue. There are only a few issues about which I feel strongly. Free speech is one, as my regular readers know. Another is affirmative action, by which I mean racial preferences—i.e., giving a candidate a plus or a minus based on nothing more than their race.1

I oppose racial preferences in education, as do 74 percent of Americans, and I have held this view for more than 30 years. My overall political views, as well as my specific opinions on many different issues, have shifted dramatically over the past three decades. But my opposition to affirmative action has remained constant.2

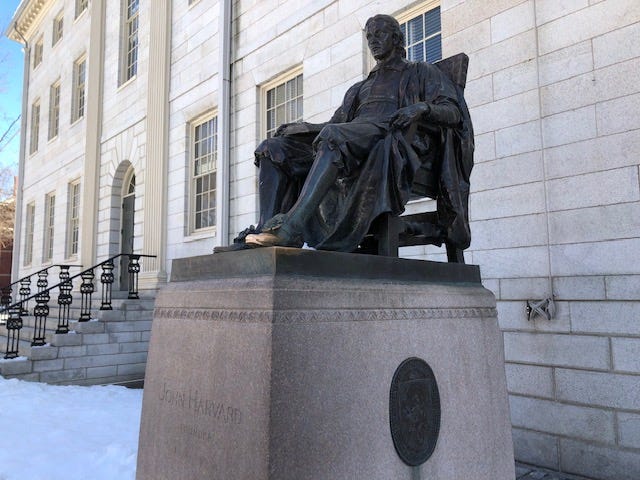

So I listened with great interest to Monday’s arguments in the Harvard and UNC affirmative action cases, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina. We won’t know the final outcomes until the opinions get issued—or, God forbid, leaked—but I agree with most smart observers that Students for Fair Admissions (“SFFA”), the organization challenging racial preferences, is likely to prevail.

At the end of the day, the case boils down to this: does using race qua race in admissions, i.e., taking into account an applicant’s racial identity as such, violate either (1) the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of “equal protection of the laws,” or (2) Title VI’s ban on discrimination “on the ground of race… under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance”?

Much of the defense of affirmative action involves touting the “holistic” admissions process used by Harvard, UNC, and peer institutions. This wonderful and multifaceted process, the universities argue, takes into account countless complex factors; race is but one of many, rarely dispositive. But as SFFA’s lawyer in the UNC case, Patrick Strawbridge of Consovoy McCarthy, repeatedly (and correctly) emphasized, college admissions is a zero-sum game:

There are a limited number of spots in the Harvard and UNC classes.

Giving an underrepresented minority (“URM”) candidate a “plus” because of their race is functionally the same as giving a non-URM candidate a “minus.”

Even acknowledging that a plethora of factors are considered under “holistic” admissions, the racial “plus” or “minus” will be dispositive in some number of cases—i.e., a candidate who wouldn’t have been admitted but for their race will get accepted, and a candidate who would have been admitted but for their race will get rejected.

The rejected candidate has been discriminated against “on the ground of race,” within the meaning of Title VI. And if the university is a state school like UNC, the rejected candidate has been denied the “equal protection of the laws,” too.

We can argue—and the parties argued in district court—over how many applicants are affected. But if applicants have a constitutional or statutory right not to be subjected to racial discrimination, and Harvard and UNC knowingly violate those rights by using race-conscious admissions, the small number of victims is no defense. We don’t excuse violations of the Constitution or laws of the United States because “only a few people’s rights” were violated.

The emphasis on “holistic” admissions winds up hiding the ball—obscuring the fact that some applicants are being helped, and some applicants are being hurt, purely on account of their race. But it also wound up harming the pro-preferences side in yesterday’s arguments: the defenders of racial preferences got hoisted by their own “holistic” petard.

Because the modern-day, “holistic” admissions process is so comprehensive, probing, and judicious, applicants who have overcome discrimination—which both sides agree is a legitimate consideration for admission, since it reflects qualities like resilience, character, and grit—have multiple avenues for sharing this with the admissions committee. They can write essays. They can ask teachers or guidance counselors to discuss it in recommendations. They can mention it themselves in interviews. A ruling in favor of SFFA would not—and should not—prevent this.

So what would a ruling for SFFA do? It would block universities from considering race qua race, i.e., race divorced from any other factors. It would bar Harvard and UNC from asking applicants to “check a box” for race and then assigning pluses or minuses to applicants based solely on the boxes checked. It would also prevent URM candidates who have not suffered significant racial discrimination from “free riding” on the experiences of those who have. Consider the following scenario.

My husband and I are a white/Asian couple raising a son who is part-Black and part-Latino (Afro-Caribbean). Our son Harlan is also privileged: he has two loving, well-educated, well-to-do parents, plus four loving, well-educated, well-to-do grandparents. Shielded by all this privilege, he will hopefully face little to no racial discrimination, especially growing up in an affluent, tolerant, even welcoming suburban community. He will hopefully not be able to write a college essay about overcoming discrimination or disadvantage.

When Harlan applies to college, should he get a benefit simply from checking the Black and Latino boxes, even if he didn’t suffer significant adversity from being Black or Latino? Much as it pains me to say this, given how much I’d like him to attend a school like Harvard or UNC, I think not. He should not be able to “free ride” off of the experiences of applicants who have suffered on account of their race—and whether or not they could do so in the past, today universities can distinguish between these classes of applicants, given how much they’ve invested in their “holistic” processes.

This is where defenders of racial preferences get hoisted by their own “holistic” petard. If their amazing admissions process is so careful and comprehensive in its individualized evaluations of applicants, “then why do you have them check a box that I'm Asian? What do you learn from the mere checking of the box?” That’s what Justice Samuel Alito asked of North Carolina Solicitor General Ryan Park, defending UNC’s racial preferences—and Park had no good answer.

Defenders of affirmative action argue that “checking the box” correlates strongly with, or serves as a proxy for, having had certain experiences—e.g., racial discrimination—and this was a key point made by the three liberal justices yesterday. But again, given today’s thorough, painstaking, “holistic” admissions process, why do you need a proxy when you can have the thing itself? Why do you need an applicant to check a box when they can instead convey their experience to the admissions committee through essays or recommendations that talk about overcoming discrimination, in much more granular detail?

Put another way, checking a URM box is no guarantee of diversity. As Chief Justice Roberts repeatedly emphasized at oral argument, assuming that people who check a certain box have certain views or a certain type of life experience is nothing more than rank stereotyping—and often unwarranted, given the increasingly complex and diverse world in which we live.

An applicant who checks the “Black” box might be a descendant of former slaves who lives in poverty in rural Mississippi, a child of a Nigerian industrialist who lives in incredible wealth on Banana Island, or our son Harlan, a child of two lawyers who lives in upper-middle-class comfort in northern New Jersey. Should all three of these applicants get a “bump up” or “tip” in admissions—even vis-à-vis, say, a child of Chinese immigrants who lives in poverty in New York’s Chinatown, or a white kid who lives in poverty in rural Appalachia? I submit not.

In the UNC argument, Justice Thomas said this to Ryan Park: “I've heard the word ‘diversity’ quite a few times, and I don't have a clue what it means.” Justice Thomas, I can explain to you exactly what “diversity” means to Harvard and UNC.

Allow me to share a story. It might sound irrelevant at first, but bear with me.

Years ago, in preparing to send their oldest son through the gauntlet of Manhattan private-school admissions (for which I had to write a recommendation letter for a four-year-old), my Asian-American cousin and her white husband talked to an “admissions consultant.” The consultant told them that elite preschools value “diversity.” My cousin excitedly told the consultant about how she’s from the Philippines, her husband’s from Australia, and their son at his tender age had already lived in multiple countries and been exposed to many different cultures and languages.

“I’m sorry,” the smiling consultant said to them about their white-looking son, “but that’s not what these schools are looking for. Your child does not offer visual diversity.”

Visual diversity. That sad, shallow, hollowed-out vision of “diversity” is exactly the kind of diversity that Harvard, UNC, and other educational institutions are obsessed with. That’s the kind of diversity these schools are seeking by giving pluses to applicants who check the right box. Checking the Black box doesn’t guarantee a “Black” experience: the descendant of former slaves, the child of the Nigerian tycoon, and our son Harlan have had radically different life experiences, and as a result, they probably hold radically different worldviews too. But here’s the one thing that all three of them can reliably deliver: visual diversity.

So in the end, what Harvard and UNC are arguing is that visual diversity is a compelling state interest. Having classrooms and admissions brochures that look like Benetton ads can justify resorting to racial classifications that we have justifiably banned in pretty much every other area of American life. The idea would be laughable if it weren’t so offensive.3

Now let’s look at “visual diversity” from the Asian-American perspective. The evidence at the Harvard trial showed that Asian Americans were disfavored even compared to whites—which is why they’re widely seen as “the new Jews,” referring to how Harvard subjected Jewish students to quotas in the 1920s and 1930s (as noted by former K&L Gates chair Peter Kalis in this persuasive piece for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette).

For example, when encouraging applications from so-called “sparse country,” or geographic areas underrepresented at Harvard, the university sends invitations to apply to high schoolers who score well on the Preliminary SAT (“PSAT”)—and uses different cutoffs based on race. White students get an invitation if they score a 1310 on the PSAT, while Asian women need a 1350 and Asian men need a 1380.4

Similarly, studies by Harvard’s Office of Institutional Research (“OIR”) concluded that the college’s admissions process disadvantages Asians—not just relative to African-Americans and Hispanics, but also relative to whites. The OIR research showed that based on academics, Asians would constitute 43 percent of Harvard’s incoming class—far higher than 19 percent, the actual percentage for the time period in question.

What might justify giving white applicants preference over Asian ones? I respectfully submit that it’s not because we would detract from the diversity of experience on campus. As I wrote in my own Harvard admissions essay years ago, trying to preempt what my parents and I feared was anti-Asian bias even back in 1991, I was a “banana” or “Twinkie” as a kid: “yellow on the outside, white on the inside.” I grew up in a largely white community, attended largely white schools, watched the same television shows as my white classmates, and spoke English just as well as they did. An admissions system trying to promote diversity of experience shouldn’t treat me any worse than my white classmates; at most, it should treat us the same (or maybe give me a little bump up, since I had “diverse” experiences like hearing Tagalog at home and eating lumpia in addition to hot dogs).

But giving white applicants a preference over Asian-American ones makes sense once you remember that what the schools are looking for is visual diversity. Having a class that’s 43 percent Asian American, even if those Asian-American students have life experiences that are as diverse or even more diverse than their white peers, is terrible for visual diversity. The fact that many of us have dark hair and dark eyes—i.e., we don’t have the greater visual diversity of white people, who have more variation in hair and eye color as a matter of biological fact—just makes things worse. See generally AllLookSame.com.

The nations of Asia are vastly different from one another—some of these countries hate each other historically “back home”—and the experiences of Asian immigrants from these nations are also vastly different. So why do extremely diverse groups with extremely diverse experiences all get lumped together under one “Asian” label? It’s the visual diversity, stupid. For purposes of the Benetton ad they’re trying to construct, Harvard and UNC have no interest in the internal diversity of the AAPI community. They just need some Asian faces for their glossy brochures—but not too many Asian faces, mind you, and certainly not 43 percent Asian faces.

I might not agree with the nine justices on everything, but I know that they are smart. I have faith in their ability to see through the smoke and mirrors being put up by Harvard and UNC. I am confident the justices will recognize that visual diversity is not real diversity—and it is certainly not a compelling state interest.

True diversity comes from within. It can’t be captured by checking a box. And I look forward to the day when the law compels our nation’s great universities to ignore superficial diversity and to focus on what lies inside each of us.

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; (3) the ability to comment on all posts; and (4) written transcripts of podcast episodes. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

I have no problem with “affirmative action” in the form of, say, reaching out to different communities and encouraging their members to apply, in order to enlarge and diversify the applicant pool. That’s what affirmative action should really be about.

I also oppose preferences in admissions for legacies, athletes, and children of donors. And the evidence in the Harvard case showed that getting rid of all these preferences, plus replacing racial preferences with an enhanced preference for low socioeconomic class, could maintain racial and ethnic diversity in a race-neutral way. I have yet to hear a persuasive argument against replacing racial with socioeconomic preference.

As a policy matter, the argument for affirmative action as a form of reparations to candidates who can clearly show they are descendants of former slaves or Native American is much stronger than the diversity-based case for affirmative action. But because of the way the Supreme Court decided Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), where there were four votes for a reparations theory and five votes for diversity (thanks Justice Powell), proponents of affirmative action are stuck defending the diversity rationale.

I use “Asians” interchangeably with “Asian Americans” for convenience, but I agree with the point that SFFA lawyer Cameron Norris made in the Harvard argument: “And we keep saying Asians. These are not Asians. They're not from Asia. These are people who are Americans. They were born in Texas, California, Ohio, Tennessee. They should not be the victims.” (By the way, I was born in Queens, New York—contrary to my Wikipedia entry, which claims I was born in Bergenfield, New Jersey, which is just a town I grew up in. I would fix it, but I don’t want to be one of those people who gets caught editing their own Wikipedia entry.)

Perfect. Congratulations. I love the term" visual diversity". It would have been amusing if Justice Thomas, after commenting on his puzzlement about what diversity is, had asked what members of the Supreme Court were examples of diversity--Kagan and Barrett or Thomas and Alito? If "affirmative action" goes down at the college level, then maybe our miserable public schools will have to challenge Black kids to their highest potential, instead of pushing them along, knowing some college will admit them even if they are not qualified. Our Black American children deserve far better education than they have been receiving for decades. it is a scandal and a tragedy.

This is fantastic.

Another point that could be made: if "diversity" were a compelling state interest, wouldn't *ideological* diversity be more important a place that exists to generate ideas than visual diversity? And yet, nobody - including conservatives, I would hope - thinks that you should be making people check a "who do you vote for?" box.