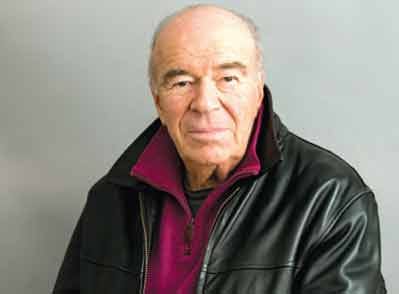

Judge Frederic Block has served as a federal judge for the Eastern District of New York since 1994. During his nearly three decades on the bench, he has presided over high-profile cases involving organized crime, terrorism, financial fraud, and the death penalty. He is also the author of three books: a memoir, Disrobed: An Inside Look at the Life and Work of a Federal Trial Judge; a legal thriller, Race to Judgment; and a nonfiction book about federal sentencing, Crimes and Punishments: Entering the Mind of a Sentencing Judge.

The best interviews feature uninhibited guests speaking freely about hot topics. So it should come as no surprise that my podcast episode with Judge Block is a fun one: he turns 90 next year, enjoys life tenure, and hails from Brooklyn. If that’s not a recipe for candor, then I don’t know what is. I hope you enjoy listening to this interview as much as I enjoyed conducting it.

Show Notes:

Frederic Block, author website

United States v. Nesbeth (E.D.N.Y. 2016)

May v. Shinn (9th Cir. 2020)

May v. Shinn (9th Cir. 2022)

United States v. Russo (E.D.N.Y. 2022)

Prefer reading to listening? A transcript of the entire episode appears below.

Sponsored by:

NexFirm helps Biglaw attorneys become founding partners. To learn more about how NexFirm can help you launch your firm, call 212-292-1000 or email careerdevelopment@nexfirm.com.

Two quick notes:

This transcript has been cleaned up from the audio in ways that don’t alter substance—e.g., by deleting verbal filler or adding a word here or there to clarify meaning.

Because of length constraints, this newsletter may be truncated in email. To view the entire post, simply click on "View entire message" in your email app.

David Lat: Hello, and welcome to the Original Jurisdiction podcast. I’m your host, David Lat, author of a Substack newsletter about law and the legal profession also named Original Jurisdiction, which you can read and subscribe to by visiting davidlat.substack.com.

You’re listening to the ninth episode of this podcast, which was recorded on Monday, December 19. My normal schedule is to post episodes every other Wednesday.

Before introducing today’s episode, I have an exciting announcement: this podcast has a sponsor. Thank you to NexFirm for sponsoring the Original Jurisdiction podcast. NexFirm helps Biglaw attorneys become founding partners. To learn more about how NexFirm can help you launch your firm, please call 212-292-1000 or email careerdevelopment@nexfirm.com.

My guest today is Judge Frederic Block of the Eastern District of New York aka Brooklyn. Judge Block was appointed to the bench by President Bill Clinton in 1994 and took senior status in 2005, but he continues to hear cases to this day, including presiding over trials. He also somehow finds time to write books, and he’s the author of three so far: Disrobed: An Inside Look at the Life and Work of a Federal Trial Judge, Race to Judgment: A Novel, and Crimes and Punishments: Entering the Mind of a Sentencing Judge.

In our comprehensive and candid conversation, Judge Block and I discussed his improbable rise from Long Island solo practitioner to federal judge, the highlights of his almost 30-year judicial career, and how judges should decide when it’s time to hang up their robes—Judge Block will turn 89 later this year, which I find hard to believe. We also talked about his views on the current direction of the Supreme Court and what he thinks of former president Donald Trump’s judicial appointees, based on having served with some of them.

And Judge Block spoke his mind, as he always does. Without further ado, here’s my interview of Judge Fred Block.

DL: Thank you so much for joining me today, Judge Block.

Frederic Block: Well, it's nice to be here.

DL: It's really a thrill. We've been friends for a long time, and it's great to have you on the show.

Let's start at the beginning. Let's talk about your upbringing. Some of this, of course, is covered in your excellent memoir, Disrobed, but for those who have not had the pleasure of reading it, was there anything in your upbringing that made you think or made your parents think that you might become a lawyer or a judge someday?

FB: Well, I knew I was not going to be a doctor because I flunked physics, and I was not going to be in accounting, that was just not in my DNA. So I wouldn't say it was a process of elimination, but I think I always was probably fascinated by the law. But I had no expectation that I would be chatting with you today, none whatsoever.

DL: So you went to Indiana University for college, I believe. What did you major in?

FB: I majored in just a general arts degree. My major was actually economics at the time. I played in the university orchestra. I also was in the Marching Hundred; I played clarinet.

I went to Indiana. It was a great choice, by accident, you might say, because it took this little New York City boy out of the city and exposed him to a whole different culture, a whole different world, and I really feel that it was just a wonderful accident that happened. It was an accident because the first two schools I applied to rejected me. So this is the only one that accepted me—I had no choice in the matter.

DL: And then you went on to Cornell, a great law school. What led you to go to law school?

FB: Well, actually by that time, the law did interest me, but we were between a couple of wars. We’ve had a lot of wars in our country, this generation. There was something called the Vietnam War, and then people don't even remember there was a war called the Korean War, which followed shortly after that.

And I was betwixt and between. I took ROTC in Indiana for a couple of years because I thought if I was going to go into the Army, I thought maybe it would be better if I went in as an officer than a line private. And then I went to Cornell. I was rejected for the rest of the ROTC program because of my eyes. I had an eye condition, which I did not think was going to disqualify me. It disqualified me from being an officer, but not from being a private. I could shoot a gun, but I couldn't go into the JAG corps and do the work. Can you believe that?

DL: Oh wow.

FB: So it turned out fine, and I'm glad I went to Cornell because Cornell was one of these two schools that rejected me before I went to Indiana, and the first one was Harvard—that's very competitive, and I thought maybe I had a shot at doing that. I went to Stuyvesant High School, which is a pretty good school, so my backup school, my safe school was Cornell, and much to my surprise, I was rejected, and I figured I had to get even with them. So I applied for law school and wound up going back to Cornell.

DL: And then how did you like law school? Did you enjoy the experience?

FB: I did, but Cornell's in Ithaca, very cold in the wintertime, which is pretty good because it made you study harder. I think that it was really something that really got into my head. I went to law school, David, during the so-called halcyon days when the Supreme Court was deciding, under the Warren Court, these landmark decisions which still resonate today, sixty years later—Gideon, Jackson v. Denno, Baker v. Carr, Miranda, Mapp v. Ohio—and people still remember those names to this day, sixty years later. And when I was in law school, and the professor was telling us that you can consider the Fourteenth Amendment, it extends from the Fifth Amendment, we went through all of these great cases as they were unfolding pretty much in front of our eyes. And that really made a big impression on me, and that hooked me into the law.

DL: You mentioned these landmark cases from the Warren Court, but of course now the Supreme Court is very different. And we won't get into any pending cases of course, but do you have thoughts on the current direction of the Supreme Court? It’s gone in a very different direction compared to the Warren Era.

FB: I write about the fact that we had this moment in our legal history and it's not the same today, and I write in some of my decisions about how we've gone in the wrong direction. It bothers me greatly. I point out, for example, mass incarceration and the death penalty—you know a lot of these things, you know how I feel about a lot of them, but the thing that bothers me, well, is that habeas corpus exists in name today, as far as I'm concerned. It's only in name, it's not in practice. The great writ of habeas corpus has been rendered nugatory by a spate of recent Supreme Court decisions, and I think that's regrettable.

So I really feel that our trajectory is not in the right direction. And we really are going downhill in many respects, from embracing concepts of freedom and justice, all those good fuzzy things that we feel strongly about.

DL: In terms of the direction of the courts, a big part of that, of course, is personnel and appointments. President Biden has appointed a record number of public defenders to the federal bench, and you've spoken out very eloquently about the importance of defense lawyers, for example, when you received the Jack Weinstein Award from the New York Criminal Bar Association. Are you encouraged by the appointment of defense lawyers to the bench? In past years, prosecutors really dominated.

FB: Well, yes, I think we need the diversity—the diversity, not only in terms of the obvious national origin and gender, but diversity in terms of experiences that people have had in the practice of law.

And I am really, pretty much to this day, a little bit of a fish out of water in the E.D.N.Y. in Brooklyn. Why do I say that? I'm surrounded by very bright people, and they're very fine judges, but their experience has not been my experience. About 50 percent of them come from what we say is “The Office”—that means they've been U.S. attorneys or assistant U.S. attorneys—or they've been at Biglaw firms, doing a lot of depositions, or some of them have had academic backgrounds. But I think I’m the only one who really had an everyday practice of law. And I think that that makes a big difference in terms of your overall perspective about things.

The diversity we need is really in that direction. We should have federal defenders. We should have people who cover the waterfront in terms of what legal practice is all about. We have a couple of new judges who were recently confirmed, and they tend in that direction.

So I’m all in are favor of that, there's no question. But that's the diversity we need, not only in terms of color or national origin, but in terms of exposure to the law, where people actually practiced law. We have very few people in my court that actually practiced civil law, that actually went to court, that actually negotiated with insurance companies, that have a real feel for the whole panoply of what the law is all about. And these are all capable people. And I think that I really make a contribution to the bench because I come from a different background.

DL: Let's talk about that for a little bit. You talk about it, of course, in your memoir, but you do have a different background. You didn't come from the U.S. Attorney's Office. You represented many, I guess what we would call “ordinary people.” You didn't work at a so-called Biglaw firm.

You did have some very interesting experiences. You represented Judge Judy, for example, as you talk about in your book, and you argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, but can you talk a little bit about your career in practice before the bench? What did you generally do, and how does it make you different compared to many fellow federal judges?

FB: Well, after I got out of law school, I clerked for the appellate court in Albany, and then I met some people there that told me about Suffolk County [in Long Island, New York]. My father had passed away just a few months before and I was looking for some direction, and I met some wonderful people that said Suffolk County is really an interesting place. It's a growing, emerging county, and I was influenced by that. And I wound up practicing in Suffolk County basically as a solo practitioner.

And the interesting thing about it is that I had a good legal background, from Cornell, obviously, and I had a clerkship background, so I was oriented to the law. When I came to Suffolk County, I had no real significant relationships there, and I really didn't know what to do to make a living, and I actually started my own practice about several months after I came there. I don't know what I was drinking that day. I literally hung up a shingle at a place called Port Jefferson and just waited for people to come knocking on the door. And I don't think people do that anymore. But it was exciting to create your own law practice, to create your own personality, to relate to people on that level.

And what happened is that I wanted to stay in touch with the law. So Baker v. Carr had just been decided, and that was the landmark Warren Court case. [Chief Justice Earl Warren said he] thinks that that really was the most important case he decided, then Brown v. Board of Education. He was a great believer in the concept of what they said in those days, inappropriately: one man, one vote. You talk about being politically correct, sixty years ago. So it's one person, one vote, equal representation for all elective levels of government.

After Baker v. Carr came out, Suffolk County had ten towns, and they each had a town supervisor who was the county board of supervisors, and they each had one vote. So Shelter Island, which had 1,100 people, had the same one vote as Brookhaven Town, which had 150,000 people. The five Eastern towns had 10 percent of the population, 50 percent of the vote. So I was put in touch with that disparity and I said, there's something about that that's wrong, and I think this might be a cool thing to do. So I really sat down and the very first complaint I wrote as a lawyer was the case challenging the constitutionality of the Suffolk County government [based] on the fact that it didn't comport with one man, one vote.

And I argued that in the United States Supreme Court. So how many lawyers do you know who can say that? The first complaint they ever drafted, they wound up arguing in the United States Supreme Court, and it led to the extension of the one person, one vote principles to all elected levels of government.

I didn't get paid a penny for it. It was a year or two before [42 U.S.C.] § 1988, allowing you to have fees representing people in the civil rights cases, was enacted by Congress. So I did all of this without a penny. I imagine if we had the right to have fees, I could have made a couple of bucks in those days. And that really came in handy many years later, when I had to appear before Senator [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan’s [judicial selection] committee. They were interested in the fact that yes, I had that case, which I think is probably one of the reasons why I'm here.

DL: So I’m curious about that. That's amazing, it's a great story: one of your early cases made it all the way to the Supreme Court. How many years into practice were you roughly when you argued before the Supreme Court, and what was that experience like? It must have been very intimidating.

FB: Well, I was 34 by the time I got to the Supreme Court, and we brought the lawsuit when I think I was 28 to 29. It took a few years, of course, to get up there. And it was—I mean, I could go on for hours talking about it, but when Earl Warren says, “Bianchi v. Griffing, Mr. Block,” and you're 34 years old—believe me, my voice was two octaves higher after that point on, but you remember that with affection.

I had a sense that would be the only time I would be arguing before the United States Supreme Court. We had Abe Fortas on the bench at that time, and he asked some nasty questions. They didn't really mollycoddle you. They treated you as if you really knew what you were talking about. And it went by like a blur. And when I heard they make tapes of these things, I think I can still get the tape—my voice was three times higher than it is right now.

But what happened in that case, by the way, is it was remanded to the circuit court of appeals. And there's a whole story about that because Warren wanted to extend the principle of that case, but they took four cases: one from a big county down in Alabama, one in a school district out in Michigan, one in a city down in Virginia Beach, and he took our Suffolk County case. They all represented different forms of government, but they all had as the core issue the issue of one person, one vote.

All of those cases were remanded for, I think, technical reasons—I think they could have decided the case then. But we found out from Warren later on when he spoke about that, that he had a 5-4 vote at that time and Marshall was going to be coming on the bench, and he was going to be replacing Harlan, and there was a case down in Texas, Avery versus Midland County that was coming up, which raised the same issue, and he decided to duck the issue here, and in the next Term, in the Avery case, he got a 6 to 3 vote. It was just a dramatic moment in the history of the evolution of the Supreme Court, the Warren Court, and the whole concept of one man, one vote, one person, one vote. And I was at the center of that. So to this day, when I talk to you about it, I say, wow, you know, maybe I belong on the bench. [Ed. note: This case is discussed in more detail in Disrobed (p. 59); Justice Marshall replaced Justice Clark between Judge Block’s case and Avery, and as a result, only three justices dissented in Avery rather than four.]

DL: Let's actually talk a little bit about that—and of course, again, you talk about this all in Disrobed, which I really commend to people. How did you get on the radar screen of Senator Moynihan's committee and the White House, given that you did have this unusual background, you didn't work at a big firm, you didn't come from the U.S. Attorney's Office? How did a lawyer at a small practice out in Suffolk County, Long Island, New York, make it to the attention of the powers that be?

FB: David, you'd make a good judge, actually, because you ask good questions. You know a little bit of the answer, since you read my book.

So I was in Suffolk County, and in those days, neither Suffolk nor Nassau had a federal-court presence. There was one federal court courthouse, it was the old post office building, which today is the bankruptcy building, a beautiful old building. So that's where all the federal cases were handled. And we had an opening for a district-court judgeship from the E.D.N.Y., I think this was back in 1984 or ‘85.

And Ed Korman was pretty much a lock. He was the U.S. attorney. He had just finished prosecuting what they called the 1% Kickback Case, where the chairman of the Republican Party in Nassau County was doing these illegal things, and he wound up going jail because of it. So [Korman] richly deserved getting elevated to the bench. He was very much an intricate part of the so-called Brooklyn Establishment or the E.D.N.Y. Establishment.

But I went to the committee, and Moynihan’s committee at that time was headed by Leonard Garment, who I think was a Republican actually—a high-minded, well-regarded person—and Moynihan was, as hopefully your subscribers will remember, extraordinary—extraordinary, yes, in many respects,

DL: A great mind, a great force in the Senate.

FB: I came to the bench because of Moynihan, and I feel pretty good about that. So I didn't get the judgeship then, but I went there—and I had to be invited, I wasn't sure I would even get invited to meet Moynihan’s judicial selection committee—and I went there, I was then the president of the Suffolk County Bar, and I went there to tell them that we have no representation in Suffolk County nor in Nassau County on the federal bench. We have no court facilities. If we go to handle a case, it's going to be in a one-room building near the racetrack. It was really an abomination.

And so I don't expect to be selected as a federal judge—I think Korman deserves it—but I have to come here to sensitize you folks because look around this room, not one of you comes from Nassau or Suffolk County. You don’t really know we have 1,200,000 people out there. There's no place else in this country of that population that does not have a federal presence. So I said I'm coming here really not to make a pitch for me—though, you know, one of these days it would be great if I was able to grace the bench—but to just sensitize you to the fact that there is a Suffolk and a Nassau County, and we need help. Because for me to come to Brooklyn to handle a calendar is a whole day lost in my life. So we are not really practicing in the federal courts. We have to do something about it.

Well, they did. And afterwards, now we have a big courthouse in Central Islip, we have a real physical presence out there, there’s a U.S. Attorney's office.

So that was it. So I got a call a couple of days later from Moynihan, and he wanted to talk to me, and I really couldn't believe it. And why? Because he said, “The knives are out to try to get me not to appoint Korman to the bench. He deserves it, but there's a lot of opposition to him because he's responsible for the successful prosecution of a prominent Republican, head of the Republican Party in Nassau County. I don't think they're going to be successful, but I wanted to speak to you because you're my backup guy.” And I said, “Well, why is that now?” We had a nice chat.

And nine years later, an opportunity presented itself when Clinton then became president, we had three more appointments by the president, and I went back to the committee, and it was really a wonderful experience. They greeted me with open arms. And I wasn't even going to go back—I figured nine years ago, forget about it, I didn’t want to be rejected again, I felt sensitive about that—but they were happy to have me there.

I came on the bench at that time with Allyne Ross and with John Gleeson. So there it was perfect, because now they wanted to be more receptive to somebody who did not come from Brooklyn and somebody—they couldn't appoint everybody from the U.S. Attorney's Office, Judge Gleeson just successfully prosecuted the Teflon Don, Allyne Ross was very much highly regarded in the appeals unit—so things just worked out that way, where they were willing to appoint somebody from Nassau, Suffolk County, and it was timing I guess that happened, and the gods were shining on me at that particular time. So it's a great story that I got on the bench that way.

DL: This podcast is being sponsored by NexFirm. If you have wondered whether launching a law firm could be the best next step for your career, NexFirm has the experience and expertise to help. Contact NexFirm at 212-292-1000 or email careerdevelopment@nexfirm.com today to learn more.

So turning to your judicial career, which has been very distinguished, you've handled a number of really important cases over the years—cases related to the Crown Heights riots, to Kitty Genovese, to organized crime, including Mob boss Peter Gotti, death penalty cases, terrorism cases. So you're now 88. You've been a judge for 28 years. Is there a case or decision that you are most proud of?

FB: I can point to a couple of recent ones, when I think back. I wrote this decision in a case called Nesbeth, which dealt with collateral consequences. I’m asked that question often, which is the decision which I feel I'm proud of, and I like this one because it had a big reach, and it really made a big difference.

I read Michelle Alexander's book, The New Jim Crow, and it’s a good polemic. She made the argument that when people get out of jail, they're not necessarily at liberty, that there are so many collateral consequences that they have to face—that in effect they’re still are in prison, but maybe without the bars in front of them. That impressed me. And then shortly after that, circumstances make these things happen, I got the Nesbeth case. And it was the classic factual dynamic that really spoke to collateral consequences: a young woman who had a bad hair day, she went down to Jamaica with a boyfriend, she came back carrying some drugs, very bad. She was otherwise an exceptional young lady. Top grades. She was going to be a teacher, she was going to be a principal. But she did commit this crime, and she had to be punished for that.

But I then asked my law clerks, let's take a look at how many collateral consequences we have. As good law clerks would do—you know if I gave that assignment to you when you were clerking, you would find the answers, right—and I was astonished that in the federal system, if I remember correctly, there are over 170 collateral consequences, loss of all sorts of privileges. Food stamps, housing, opportunities like the right to vote, the right to drive a car. And each state had their own collateral consequences, and they add up to 50,000 when you added all the states together.

So that animated me to write this decision in Nesbeth, and I feel really pretty good about that because I think it may have had a bit of an impact where people are more sensitive to considering collateral consequences when it comes to sentencing. I wrote that this should be part of the [18 U.S.C.] § 3553(a) sentencing mix. I think it has not been overruled. I know that in the E.D.N.Y., the Probation Department in every [presentence] report addresses the issue of collateral consequences.

I think that Nesbeth has sensitized the country and the judiciary to the fact that when you get out of jail, you have really tough times ahead of you. And I apply that as often as I can. I ask the lawyers, tell me what collateral consequences [apply]. The obvious ones, difficulty in getting employment, we understand those types of things, but there's so many out there. So I really am very much committed to getting people to be sensitized to the fact that when somebody gets out of jail, they have a tough time of it. They have a tough time of it sometimes getting employed even if they're not in jail.

That’s one [decision] I feel particularly strong about, and that was one I think I did a few years ago. I've lectured around the country about it, and I really feel that that was the one that I made my major contribution to the bench on.

The other one was one that I decided recently as a dissenting opinion when I was sitting as a designated judge for the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in a case called May versus Shinn. And there I was in the dissent, and I wrote a couple of decisions, and you'd have to read that whole majority, concurring, dissent, additional concurring opinions, to get a real feel for what happened to poor Mr. May. In the Arizona state court, he was convicted of fondling some young kids, he was a swimming coach, and I don't condone that, and the trial was very, very much up in the air. It was a hung jury. The judge declared a mistrial, and then the bailiff came back in and said that I just spoke to the foreperson, they want to give it another shot. The defendant's lawyer had to decide whether to walk out of the courtroom, which he was entitled to do, or say, okay—well, he made a decision that resulted putting his client in jail for the rest of his life.

The Arizona state court judge sentenced May to 75 years. He was 35 years of age at the time, and it was a habeas case, and originally, when you read it all, I was on a panel with Judge Friedland and Judge Ikuta. Judge Ikuta is very much a traditionalist. Friedland agreed with me that we should grant habeas, there were reasons to do this. He had been in jail for 10 years. He was freed by the district-court judge who granted habeas. He was at liberty, and we were going to keep him at liberty rather than to send him back to jail for the rest of his life. Now, for sure, what he did deserved punishment, but not for the rest of his life. So it really reflected a disproportionate sense that we have where we just throw out these numbers and we are just not realistically on top of what the realities of life are.

This guy didn't belong in jail for the rest of his life. Ten years he had been in jail. We can argue maybe he should have been jailed a little longer, maybe a little less, but the rest of his life? When you read that, what's remarkable about it is that Judge Friedland originally voted to grant habeas with me and then she changed her vote on the motion for reconsideration. That whole change of vote she was apologetic about, and she wrote that I feel that the constraints I have under habeas review compel me now to deny habeas relief, but I agree with Judge Block that the system of justice we have, that this does not reflect well on our system of justice, very compelling words. And I took that and I really ran with it when I wrote a concurring opinion talking about the lack of humanity since the halcyon days of all these wonderful Warren Court decisions, where have we gone from that day where we put this guy in jail for the rest of his life because of the strictures of habeas review?

So I would like people to read that decision because it really, to me, is a telltale example of how we've lost our sense of humanity, we've lost our concept of justice, and we have to get a handle on that because we have the largest incarceration rate in the world per population. We have the death penalty, the only so-called Western civilized country that still has the death penalty. I don’t know whether the Philippines does—you can tell me, maybe yes, maybe no—and we have problems with guns, we know all of that, with mass murder. We could talk endlessly about all these things. But what we lost is that we're just tossing out telephone numbers—five years mandatory minimum, 15 years mandatory minimum, and I think we've lost our sense of humanity in the process, and I feel badly about that.

DL: So I was just curious, Judge, I did look it up. The Philippines no longer has the death penalty, but of course under the last president there were a lot of issues [with] these extrajudicial killings where people were basically getting the death penalty without any due process, where they were being killed for supposed drug violations by police without even a trial.

So I think despite the defects or shortcomings of our own justice system, there are definitely countries that have it worse. But the two opinions you've highlighted have contributed to a very important discourse about criminal justice reform, and I think both the right and the left may be coming around on this, so we shall see, but I think your contributions have been important here.

FB: I think there is a congruence with the right and the left. We bandy these labels about, I hate them because it really does not further the goals of justice or common sense. The interesting thing about the Nesbeth case is that when I write that, I'm not thinking I'm a liberal or conservative, I just think that I'm trying to do something which seems fair-minded and the correct decision to make. The Heritage Society supported it. I had the conservative press support[ing] that decision. They thought it was right. They thought it was fair. And they're also sensitive about mass incarceration.

So we had the recent enactment, the bipartisan legislation, the First Step Act, which was really this wonderful piece of legislation. They came out of a fractured country over the last few years. And there the Republicans and the Democrats and the conservatives and liberals all coalesced, realizing that we have to do something about mass incarceration. The conservatives were particularly concerned about the fact that we spend $81 billion a year to support our prison system, and the liberals, for lack of a better word, had a sense that this was just the way to go. So we coalesced [around] that and we have now a little bit of compassionate relief for people who deserve a second look or a second chance.

So the last decision I wrote, I think I gave you a copy of it, was the Russo case, where we talk about compassionate release, and I ended it by saying that Congress should be lauded for enacting the First Step Act and the judiciary should wholeheartedly embrace it because it's a touch of humanity, it's a touch of a sense of justice that really should be the bellwether of our judicial system instead of harsh mandatory minimums or just telephone numbers, because it's politically a sexy thing to do.

I feel strongly about that. If you take Nesbeth and you take May and you take Russo, you pretty much know about Judge Block. The question is, at the age of 88, should I say I've done enough time to hang it up? That’s a whole different conversation.

DL: I was going to ask you that actually: how do you know when you feel it is time to step down? I think anyone who reads your opinions or listens to this podcast will realize that at almost 90 you are still sharp as a tack, but when is it time to hang up the robes or retire the gavel?

FB: Objectively, David, I could support a mandatory [retirement] age law. I don't think it should be 60 or 70, 75, 80, maybe even on the Supreme Court, 80, 85, whatever. And I think there are certainly cogent arguments that there should be age limitations. Having said that, there obviously are some exceptions where people are able to function even at my age, and I feel really fortunate. I don't have a lot of control over these things. None of us do. But I hope that this podcast will say that I can still mentally do it, and I know I can do the job.

So what do you do? It's very difficult. You have a real responsibility. Your law clerk's not going to tell you. Your colleagues generally are not going to tell you when to do it. I talk about Judge Thurgood Marshall and Judge [Jack] Weinstein because Weinstein, I think I may have told you this, when he was 70, he wrote to Marshall, who was just about ready to retire, and he asked him, when should you leave the bench? Because in New York, 70 on the state level was the cutoff age, and he was thinking about maybe being on the state court of appeals. And Marshall wrote back and he said, “Jack, you can't trust anybody except your family, your own sense of your own self, you have to look inwardly. And your neurologist. I consulted my neurologist last week, and I'm sending in my resignation to the Supreme Court next week.” And he passed away six months later.

It's a very internal, personal type of thing. The truth of the matter is you try to get some feedback from people like you who are not my law clerk, and you have a rich reputation of being objective and writing about things, which really cuts across the legal firmament. So I would look to your thoughts also. If you told me, “Judge, maybe you should hang it up,” that would weigh heavily on my mind.

I'm going to probably stay here for another year, but it's very much in my head because I am sensitive to when the lawyer walks into court and sees a 90-year-old judge on the bench, it adds an X factor. His client's going to turn to his lawyer and say, “Are we okay here?” When you become an X factor, you have to really think about when is the right time to leave the bench. It's a very difficult thing. I'm not going to do it next year, but I'm beginning to wonder what the right number is when I think of 90. But Leo Glasser, who we visited this week when you came, is 98, going to be 99.

On the other side, I feel that if I would've left the bench a year or two or three [ago], I would not have had these decisions I spoke about today. So what do I do? We now feel that the federal judiciary is the bastion for the United States concepts of democracy that we've really held up firm and decisions that have come out of the federal court over the last year or two really reflect the genius of the founding mothers—I always like to say mothers instead of fathers—that they said, yes, we need an independent federal judiciary to protect us against the king, and we're seeing that play out today in real time.

And I can talk about Trump appointees if you'd like also, I have some thoughts about them.

DL: Oh go ahead actually, I'm curious.

FB: I have sat for the last 17 years as a visiting judge by designation on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the last two times out there I sat with some of Trump’s appointees. Now they were young, and there's certainly an argument to be said that you maybe should have a little more life experience before you go on the circuit court of appeals. But what impressed me is that they were all extremely capable, with incredible credentials—better than mine, better than most of my colleagues. They were selected by Trump's counsel, and he really [wanted them] philosophically Federalist, yes, conservative, young. But having said that, he was committed to making sure that they were A-1 in terms of their qualifications, and they were, and it was really kind of a pleasant surprise to sit with them.

One was 42, the other was 39. They were very respectful of me. They made me feel like I was 150 years old. And we got along fine. I wrote an opinion for the court, I did have to write one dissent because I felt that they didn't know what summary judgment was all about, but it was all very respectful.

And in the E.D.N.Y. we have very good appointees also. I don’t know if it’s [Senator Chuck] Schumer’s influence, I don’t know that Trump cares or doesn't care about New York, I don't know really what Trump is all about, quite frankly, I don't want to engage in those conversations. But the [fallout] is that we have a quality federal-court bench, even with the so-called Trump appointees

So for people to think that because it was a Trump appointee, this person is not competent, is just wrong. And for people to think that because it’s an Obama appointee, this person is great, is wrong. I've sat with some Obama appointees without mentioning names that really didn't have a clue, but they had the right, for lack of a better expression, ethnic or nationality, pedigree, whatever. They look good in that respect to the population. So you really want to have a federal bench that prides itself on quality. There are a lot of variations on the theme, which you can't politically control nor should you, but I think we're not in any danger, and that goes for the Supreme Court also.

I make no qualms about the fact that I am a Democrat from Suffolk County, I pride myself that I haven't been voting for Republicans, I can say that too, right? But it sounds kinda silly to even say that. But the important thing is that I think we have really a high-minded group of federal-court judges. When I see judges from South Dakota, North Dakota, West Virginia, Arizona, I'm always impressed with the consistency of their abilities and their commitment to doing the right thing. I feel badly that the public does not understand that. If they would sit with us on the Ninth Circuit and they would see how hard the judges work, and even on the E.D.N.Y., they try to get it right, to try to do a decent job, they would have respect for the federal judiciary more so than even the way it is right now. For attacks to be made against the federal judiciary is something that saddens me because it’s the bedrock of our democracy.

DL: Well, this is actually a good transition point to our final four questions, which are standard for all interviewees.

FB: You're going to have to cut this podcast down ‘cause I'm talking too much. This is one of the problems when you get to be an 88-year-old judge, you talk too much.

DL: No, we'll be good, Judge. So let me ask the first question: what do you like the least about the law? And this can either be the practice of law or law as the abstract system of justice.

FB: So I have one broad reach, and one that's more focused and specific about the actual practice of law.

I have a real problem with the disproportionate grip that Congress has on the judiciary. We're supposed to be the third branch, we're supposed to be an equal branch, but our budget is made by Congress, the statutes are created by Congress, and Congress passes mandatory minimums that impose upon the sentencing discretion that judges I think should have, without Congress being involved in that process. And you know what troubles me: [in] 20 percent [of cases] now we have mandatory minimums, between our drug cases, gun cases, child pornography is politically a dynamite issue—10 years, 15 years, 20 years mandatory minimum. And Congress can just take over the entire judiciary, theoretically they can impose mandatory minimums in every case.

Right now we're at the 20 percent mark. I don't want to see it go higher than that. But Congress's grip on the judiciary is, I think, regrettable. Their motivation is political; our motivation is to try to do the fair thing by human beings. There's a disconnect there. That's the global concern I have about the law.

As far as specific is concerned, I'm troubled about the fact that in the big cities like New York, you can't get effective legal counsel unless you are a major corporation. And yeah, the big firms, they do have some pro bono work, some do a better job than others, but when I first got on the bench, the big corporations were charged about $400, $500, $600 an hour, then $1,000, then $1,200, it’s never going to go down, now it’s $2,000 an hour. So what it is is that the major law firms you write about in your blog all the time, these Biglaw firms, they're not there for the everyday person. They're there for the big corporations. And I think that probably in the more rural communities or like in Suffolk County, there's a different mentality, where the lawyers there have a little more sensitivity to helping people out without necessarily saying, you're going to pay me a thousand dollars an hour.

That bothers me. It's probably more a big-city type of problem. My law clerks who go with the big firms I feel badly for, some of them are so-called big firm material, and one or two become partners. But I think I’ve had only one so far in 28 years who became a partner in a so-called Biglaw firm.

Most of them are going there because they start to make more money than the judge makes and they economically have to pay their school debts. And there's a real logical reason for them to do that. But they mostly hate it. They're not treated in a way which reflects a good sense of humanity. I think you have a good sense of that also, they're basically slaves for the hourly rate, and they're judged on that basis, and maybe once in a blue moon they may make partner, but not often, and they're really cast out after five or six or seven years.

They wind up okay. Many of them go in-house here, in-house there. There is a tendency these days for these wonderful lawyers who have been with the big firms to branch off into smaller so-called boutique law firms, 40 or 50 or 60 lawyers. That's where I would go if I was going to be a New York lawyer, there's no question about it. They just have a much better grasp of the reach of law, more sensitivity to representing human beings and not just big corporations. So those are basically the two concerns I have.

The other thing is, I sort of favor the British system of barrister/solicitor, and I think that on the civil side we see lawyers who come to court who are ill-prepared. It creates a lot of problems for us, and I feel badly about that. On the criminal side, not so much, the criminal bar, they’re pretty savvy, they're pretty well exposed to the law. And on the federal side, the U.S. attorneys are very knowledgeable. So when you have a criminal trial, it's usually an easy case to handle in terms of the fact that you are dealing on a high level in terms of interacting with really competent lawyers who are on top of their game. Not so with the civil work. We get people who really don't belong in the courthouse, we need more training for that. So this is sort of a long, long answer to your short question.

DL: My next question, related in some ways to what you were just discussing: what would you be if you were not a judge? Or a lawyer, I would say, because if you were not a judge, you said you would be at a boutique. But let's say you can't be a judge or a lawyer. What would you be?

FB: Obviously I was attracted to journalism, ergo a couple of books I've written, right? And what you’re doing really would attract me, there's no question about that, because I have a bit of a creative vibe, I suppose, and that gives me the opportunity to exercise that creative talent that I have. And the music, of course. I wrote an off-Broadway show some years ago, and I really would like to be Irving Berlin. Now, having said that, my clerks don't even know who Irving Berlin is! The generation gap is incredible. George Gershwin, maybe. They all know Mozart, they know Beethoven, but a lot of them don’t know Irving Berlin. But I think that to be in that world, to create the music and the lyrics that some of these great songwriters have done, is something that always attracted me. So it would either be journalism or maybe if I was lucky enough to really get a couple of good gigs on my musical world, I would be a person who'd be writing more Broadway shows.

DL: I would like to, just again, remind readers you've written three excellent books, which we unfortunately didn't have the time to talk too much about today, but Disrobed; you have a novel, Race to Judgment, which has accompanying music; and also a book about sentencing, Crimes and Punishments: Entering the Mind of a Sentencing Judge.

So my third question: how much sleep do you get each night?

FB: That's a difficult question because it depends on whether you mean continuous [or in total]. So it’s not surprising that at the age of 88, it's rare that you sleep straight through eight hours. But I'm not doing so bad actually, I try to cobble together eight hours, but I do have to get up once in a while during the evening. Fortunately, I'm in pretty good shape all around, but I try to put together eight hours of sleep. I usually go to sleep at 12, 12:30, 1 o'clock, and get up at 7:30, 8, 8:30.

DL: My final question: do you have any words of wisdom for listeners who look at your life and career and say, I want to be Fred Block?

FB: So I used the word “rejection,” and many years ago when I was representing a school district, I used to go to school board meetings at night. There was one member of the school board, his name was Arthur Howard, I remember the name many, many years later. And this guy, he would call up the White House every time he had a question to ask about the school-board law, and he was just outrageous. And I confronted him one day saying, “Arthur, you know, you seem to have no shame, aren’t you embarrassed?” And he said, “No—these people talk to me, and I get things done.”

Well, anyway, fast forward. I really believe that you have to have the capacity, if you feel strongly about it, [to not] worry about being rejected. I wouldn't be here today if I didn't go down the third time after being rejected twice by Senator Moynihan’s committees for reasons which I did not personalize. I was not going to go back the third time, I figured I was a two-time loser already, third strike and you’re out, and I was encouraged by somebody who said, “Don't be silly.”

And so I really reflect upon that, if I was going to allow the fact that I was rejected twice when I went to Senator Moynihan’s committee, then I wouldn't be here today. And I look back on my life and I remember that so many times when you were worried about the press rejecting you, other people rejecting you, people saying bad things about you, and I realized that you've got to be able to just do it. If you feel strongly about something, don't compromise your integrity for fear of rejection.

But it's easy to say that when you're 88, maybe it's not so easy to say that when you're 28, but that's the one thing that I take away in terms of my own personal life. So many contacts, so many involvements I've had, so many enriched experiences I've had, have been because, for lack of a better word, I just had the courage of my convictions and commitment, and I ran the risk of being rejected. Judge Judy, I wound up having dinner with her because I called her up. Just last week, I contacted Steve Cohen of the New York Mets, I didn't know him, but I thought he could be helpful to me in terms of one of my book projects. That didn't turn out to be the case, but I got a hold of him, and I’m having dinner with him. So it's so cool when you really feel that so what, so you get rejected, big deal. We're not going to live forever, just go for it. So that's what I’d like to leave you with, if that makes any sense.

DL: Those are excellent words of wisdom. And again, I'm so grateful to you, Judge, and my readers are for your time and your insight. Thanks so much, Judge.

FB: David, it's always a pleasure to be talking to you.

DL: Thank you to Judge Block for joining me. As you can tell from our lively conversation, he remains a font of energy and inspiration. If you haven’t already, check out his books, including Disrobed, his insightful memoir, and Race to Judgment, his page-turning novel.

Thanks to NexFirm for sponsoring this Original Jurisdiction podcast. NexFirm has helped many attorneys to leave BigLaw and launch a firm of their own. If you would like to explore this opportunity, contact NexFirm at 212-292-1000 or email careerdevelopment@nexfirm.com to learn more.

Thanks to Tommy Harron, my sound engineer here at Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to you, my listeners and readers, for tuning in. If you’d like to connect with me, you can email me at davidlat@substack.com, and you can find me on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn, at davidlat, and you can find on Instagram at davidbenjaminlat.

If you enjoyed today’s episode, please rate, review, and subscribe to Original Jurisdiction. Since this podcast is new, please help spread the word by telling your friends about it. Please subscribe to the Original Jurisdiction newsletter if you don’t already, over at davidlat.substack.com. This podcast is free, as is most of the newsletter content, but it is made possible by your paid subscriptions to the newsletter.

The next episode of the podcast should appear two weeks from now, on or about Wednesday, January 25. Until then, may your thinking be original and your jurisdiction free of defects.

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; and (3) the ability to comment on posts. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.