Free Speech, Wokeness, And Cancel Culture In The Legal Profession

Judges Lisa Branch and James Ho shared their insights with me in a written interview.

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking on the button below. Thanks!

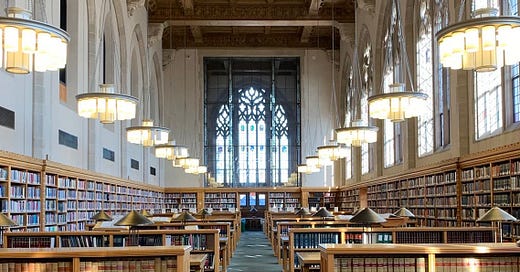

Last week, I made my way up to Yale University for an event sponsored by the William F. Buckley Jr. Program, “Is Free Speech Dead On Campus?” It featured Judges James Ho (5th Cir.) and Lisa Branch (11th Cir.) in conversation with Professor Akhil Amar of Yale Law School, followed by a wide-ranging discussion with the (standing room only) audience.

Inspired by that event, I invited Judges Branch and Ho to participate in a written Q&A with me. They kindly accepted my invitation, allowing them to share and expand upon some of their points, and our discussion appears below. I thank them for their time, their insights, and their commitment to the cause of free speech.

DBL: It was wonderful seeing you both at the Buckley Program event at Yale last week. Thank you for schlepping all the way up to New Haven—on a rainy, dismal day—to talk about an issue that’s so important to all of us.

JCH: Great to see you there. I was surprised how many students, liberal and conservative, told us how much they liked the event. Some even said it was the best event they’d attended at Yale.

I was happy to hear that, but also sad. Happy because it shows people still crave open dialogue. But sad because it felt like serving a modest meal to the starving. A sad reflection of the state of free speech on campus today.

People want open dialogue. But we’re afraid to speak up. We don’t want to be canceled by the mob. So we self-censor. And people are tired of it—tired of being afraid.

We need more of these discussions. That’s why we accepted your invitation to discuss these issues on the record. Judges are genetically press shy, and I’m an introvert, to boot. But Americans of good faith need to talk to one another. The more conversations we have, the more we’ll learn that we may disagree on many important things, but there’s much more that unites us than divides us.

That’s why I opened my remarks by talking about naturalization ceremonies. They remind us that what binds us as Americans is not a common race, religion, or political viewpoint—but a common hope for the future.

ELB: David, I truly appreciate that you were willing to brave the elements and travel to attend the event in person.

I was quite pleased with the number of students who crowded the room and how engaged they were in the topic. Like Jim, I was surprised at how many told us they appreciated the opportunity to learn more about our perspective. I must admit that I had steeled myself for the possibility that we would be met with hostility; I have never been happier to be wrong. I walked away from campus far more hopeful than I expected. And I will be happy to return to Yale early next year, this time to the law school, so that we can continue the dialogue. I hope the next event is as positive an experience as this one was.

DBL: You’ve touched on what I wanted to ask about next, but let me frame it more directly: why are you taking all this time, away from your judicial duties and your families, to travel across the country talking about free speech?

JCH: I do zealously guard my family time. So if cancel culture was just a college thing—if it were something you endure a few years and then leave behind after you graduate, like bad cafeteria food and cramped dorm rooms—I wouldn’t have gone to Yale last week.

But there’s a troubling new development in the legal profession. I see more and more lawyers, especially young lawyers, with their careers threatened for nothing more than having certain viewpoints—typically conservative and Christian viewpoints.

Cancel culture has become a cancer on our culture. Students see how folks behave on campus—not just other students, but professors and university administrators. They learn all the wrong lessons from it. We launch them into the world. And guess what happens next? They treat employers, co-workers, and colleagues the same way. What happens on campus doesn’t stay on campus.

Powerful law firm leaders and tenured law professors from top law schools are now telling reporters—typically off the record—that they’re scared of the associates and the law students. Just look at what happened last week. The same week we spoke at Yale about free speech and cancel culture, you reported on the latest explosion of intolerance at major law firms.

I’ve always enjoyed counseling young (and not so young) lawyers on their legal careers. But lately, too many people have come to me because they’re concerned, not about career development, but about career destruction.

This is not America. This is not the Constitution. I swore an oath to defend the Constitution. And that oath is not limited to judicial opinions.

ELB: I agree with Jim on all fronts. It is true that our busy schedules make travel difficult; however, I always make time for important occasions. And standing up for free speech is pretty near the top of the list.

If we don’t make this stand, who will? With life tenure comes a measure of security. Perhaps we are the last line of defense. As federal judges, we swore an oath to the Constitution. Of course we are giving speeches about it.

Somewhere along the way, we lost sight of the founding principles that make our nation great. Our people are exceptional, but we are not perfect. Sometimes we say things inartfully. It’s how we learn to hone our opinions and perfect our arguments. In the past, we excused missteps; today, we assign malicious intent. Instead, we need to afford people a moment of grace. It’s time for cancel culture to stop and open debate to return.

As judges, we have a special relationship to the law and the legal system. I have seen firsthand how the infection has spread to the legal profession. Law firm partners are struggling to navigate management challenges in our new “woke” culture. As mentors to our law clerks, we want to ensure that their career paths aren’t cut short because of the cancel-culture poison that has infected our profession (and many others). So it makes sense for judges to travel to schools to talk about free speech and ensure young people understand how far our country is straying.

DBL: Free speech often gets cast as a “liberal versus conservative” issue. But as a judge, Judge Ho, you’ve defended free speech from all along the political spectrum—for example, in favor of a student who objected to being forced to transcribe the Pledge of Allegiance and listen to the Bruce Springsteen song “Born in the U.S.A.,” or in favor of a citizen journalist who was arrested for asking questions of the police.

Why is free speech not a partisan issue? Why should we all care about defending free speech?

JCH: A principle is not a principle until it costs you. In that sense, free speech is like democracy: If you only believe in it and fight for it for folks you agree with, then you really don’t believe in it at all. That principle captures so much of what I have loved about America since I was a kid—that it doesn’t matter who you are, where you come from, or who you look like, you have the same rights and opportunities to speak and to succeed in America as anyone else.

We’re all creatures of our past experiences. So I’ll mention just two of mine here. One was co-founding my high school newspaper. I developed an early passion for journalism and law and policy, and for our commitment to free speech and open debate. I originally enrolled in the Northwestern journalism school, before I got off the waitlist at Stanford and went there instead.

And that leads me to my second passion—equality of opportunity. I’ll never forget my college advisor telling me that, after all my hard work, my grades and test scores and activities and everything else, I should be accepted at my top choice of school—if only I weren’t Asian. Things worked out in the end. But it was bumpy.

That’s why I volunteered on the Prop 209 campaign before law school. It’s why my first three arguments as a young lawyer were all First Amendment cases.

Cancel culture directly implicates both of these principles—free speech and open debate, and nondiscrimination and equality.

These are foundational principles for our country. To begin with, the First Amendment protects the freedom of speech. Yes, it applies only to the government. It doesn’t require private citizens to respect speech. But if you think that’s the whole story, I would suggest that you have an impoverished understanding of what it means to be an American.

Remember the old debates between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists, which I discussed in my Kentucky speech. The Federalists advocated a federal government that would unify the several states into one great country, while the Anti-Federalists argued that it would be impossible to have a republic this large and this diverse.

From that debate, we got a Constitution based on freedom of speech, federalism, and respect for diverse viewpoints. We have a political system and a legal system to resolve our differences. And we would work together as one nation under God. E pluribus unum.

I’m glad the Federalists prevailed. But I worry that the Anti-Federalists may ultimately be proven right.

What’s we’re seeing now is antithetical to America, and to the academy. We’re no longer content to simply engage with one another and resolve our differences in the political sphere—we expel people from social and economic life. We live in a culture of cancellation, not conversation. We don’t talk—we tweet. We don’t disagree—we destroy. It’s unsustainable and, I fear, existential.

ELB: The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech.” Nothing about it is partisan. Currently, however, the main speech that is being silenced, at least in most law schools and law firms, is either conservative or Christian. And so, people try to paint the issue as a political one.

But memories are short. The Supreme Court has often ruled in favor of protecting speech that is far from conservative such as flag-burning, communist speech, and hateful language at service members’ funerals. Right now, conservative speech is in the crosshairs, but we should be mindful that the pendulum often swings. Everyone should have an interest in protecting speech, regardless of ideology.

DBL: The topic of the Yale event was “Is Free Speech Dead on Campus?” When you were college or law school students, what was your experience with this issue?

ELB: When I was in school, it never occurred to me that there might be topics that were off-limits. We discussed everything that popped into our heads, from the sensitive to the mundane. Of course, campuses were generally not so severely divided along political lines back then. We were interested in politics, but we did not allow it to affect friendships. We approached discussions with open minds. Sometimes we changed our minds after listening to others argue. And my feelings were never hurt after hearing a contrary opinion. We weren’t tougher skinned; it just never occurred to us that words could cause lasting harm.

JCH: I had a great experience—both at Stanford and the University of Chicago Law School. It’s not because no one disagreed with me! But the environment was very different. People could debate and discuss and challenge and befriend and learn from one another. So it saddens me when I go to campuses today and hear that students no longer want to even talk to and befriend people who disagree with them. I’m sad that students endure such extreme intolerance—not just from their fellow students, but from professors and university administrators. And that attitude is now infecting the rest of the world.

DBL: Campuses have changed a great deal since we were in college or law school. You have more women, people of color, and LGBTQ people on campus than ever before.

But it’s not enough to just admit them and then let them fend for themselves. Your critics ask: how can you defend the inviting to campus of speakers who make these historically marginalized groups feel unwelcome or even unsafe?

Defenders of free speech often draw a distinction between “mere words” and “physical harm.” But if an anti-LGBTQ speaker comes to campus and spews hate, and a transgender student takes their own life as a result, wasn’t that harm far greater than, say, punching that student in the arm?

ELB: In response to your hypothetical, hate speech is despicable. In a similar vein, at the Yale event we were asked about how best to respond to the argument that “words are violence.” Any speaker espousing violence deserves condemnation. But there’s a lot more lurking behind both the student’s question and yours.

These days, we seem to take shortcuts with arguments by using broad labels, such as characterizing opposing viewpoints as “violence” or “hate speech.” Simply because someone disagrees with you does not mean that their words fall into these extreme categories.

So let’s get away from broad labels and define terms more specifically. Why do critics claim that speakers with opposing viewpoints are “committing violence” or “spewing hate”? What they aren’t saying out loud is that the speakers they condemn typically are conservative or Christian. The liberal students often don’t know the specifics of what the speakers will discuss; rather, the students just want to prevent them from coming to campus to present their views. And the most effective way to do that is to use an emotionally charged label, however false it may be.

JCH: I despise bullying. I experienced bullying as an awkward Asian kid. But we should be able to draw a distinction between bullying and good-faith dialogue, and I would err on the side of presuming good faith—bullies typically aren’t too hard to spot.

I wouldn’t attend an event that “spewed hate” to anyone, and if I were leading a student organization, I wouldn’t invite a speaker who spewed hate. But let’s be honest. Some of the most hateful people right now are the ones canceling speakers.

If we’re truly worried about making sure that everyone—everyone—feels welcome on college campuses, we should be concerned about welcoming conservatives and Christians as well as other groups. And we should be concerned about discrimination against Asians as well as other groups. Otherwise, the sincere concerns you’re referencing—they’re not sincere after all, they’re just a rhetorical move.

DBL: Students who oppose a particular speaker coming to campus have their own free-speech rights to protest; they aren’t required to say or do nothing in the face of what they perceive as hateful speech. What options are available to them?

ELB: When I was in law school, Holocaust deniers were gaining traction and were being invited to deliver speeches. A few of my classmates and I were horrified when we learned about one such event nearby, and we struggled with our response. We didn’t organize a boycott, picket the event, or attend the event and ask tough questions—we stayed home. And it turns out that a lot of people had the same idea. And because no one showed up, the speaker was never invited back. By staying away, we showed that the speech was truly unpopular.

I object to students shutting down speakers. Other forms of protest are certainly available—attend and ask tough questions, hold up signs outside the event, stay home, or organize a competing event. So why are students turning to disruptions rather than these other forms of protest? I suspect that students are turning to disruptions because they are afraid that the speech is not as unpopular as they would like. And that approach should cause grave concerns.

JCH: There’s a big difference between protesting and disrupting. Personally, as a student, I always preferred listening and engaging and then making up my own mind. I heard from every speaker I could, across the spectrum. And I learned a ton as a result. I always saw much more value in engaging over protesting. Engaging gives you the chance to learn when you’re wrong as well as persuade others to come your way.

But protesting is certainly your right. And it’s certainly better than disrupting. And that’s where you cross the line—when you start to disrupt and interfere with someone else’s right to speak or listen.

That’s what we were seeing at Yale last year. Administrators threatened a student’s legal career based on his viewpoint and membership in the Federalist Society. They even said things would be even worse for him if he were white. Meanwhile, they stood by and did nothing while students actively threatened and disrupted others, even one of their most respected law professors, from speaking and listening. Police were present, yet they had to call for backup. There’s been some denial about what happened, but the conservative and liberal speakers wrote a joint op-ed that folks can read for themselves.

The story they tell is one of an intolerant and indefensible educational environment if I’ve ever heard of one. And it’s one I want nothing to do with.

DBL: On that subject, you have famously—well, famously at least within our little corner of the legal world—instituted a boycott of Yale Law School when it comes to clerkship hiring. More specifically, you have declared your intent not to hire students who matriculate at YLS from this point forward (i.e., not current students or alumni).

Why is this the best solution? Isn’t it just discouraging conservatives from going to Yale Law, where their voices are sorely needed?

JCH: My complete reasoning appears in my Kentucky speech, which has been published, but I’m also happy to try to summarize here. What’s the point of any boycott? Boycotts always hurt the boycotter as well as the boycottee. So why are you forgoing transactions that you’ve been engaging in—and benefiting from—for quite some time? You’re doing it to make a point—to spur change in an institution. That’s why you saw boycotts during the civil rights era, and why labor unions go on strike today. They do it to induce change.

Why is Yale boycotting U.S. News? There are conflicting reports, but whatever the reason, it’s helpful to compare what we’re doing and what Yale is doing. We’re both trying to use whatever influence we have to spur change. If anything, what we’re doing is more modest: Yale is trying to make U.S. News more progressive, while we’re just trying to hold Yale to its own commitment to free speech and rigorous debate.

Remember Sweatt v. Painter. What would we say if a judge refused to hire from that law school during that era—even though that would hurt the white students there who opposed segregation?

I’ve said from the outset that, if there’s a more effective way to restore free speech, I’m all ears. But if you talk to students on campus these days, law schools are in “crisis,” to quote Professor Kate Stith. And the situation seems to be getting worse.

I didn’t come up with the boycott idea. I’ve talked to countless students and recent grads who know much better than I do how bad it’s gotten on campus. Including recent Yale law grads. They’re the ones who first suggested the idea to me—and to the late Judge Laurence Silberman (D.C. Cir.), too, I imagine.

Since our announcement, we’ve heard from students, alums, and faculty that the national conversation has in fact influenced the institution. Vivek Ramaswamy, a Yale law grad who literally wrote the book on these issues, has cited our efforts and explained that external pressure is often far more effective than internal efforts to drive change. Because incentives matter.

We’ve also heard from countless federal circuit judges around the country that they support what we’re doing—even if they don’t plan to do so publicly.

You asked us last week whether a private law school has a First Amendment right to be a “woke” law school. And I said: Of course they do! But people deserve to know what you are, before they go there. Are you a free speech school for everyone? Or are you a school for only one segment of the population?

The point of the boycott is to call that question now. Because schools shouldn’t say that they’re one thing, when they’re in fact another. Be transparent about who you are. Be honest with people. And then the market can respond accordingly—students, judges, everyone.

The boycott will either spur change—or it won’t. If it spurs change, great. And if not, then at least the market is on notice. You put it well last week, in a different context: “You walked into the lion’s den—are you really surprised that you got eaten?”1

ELB: Is our approach the best solution? We’re open to other ideas, but it’s the best one we’ve found. We did explore other avenues.

When I first learned of the disrupted event at YLS, I was horrified. And I was not alone. Judge Silberman—a great judge and a patriot who recently passed away—sent an email urging all federal judges to consider whether the participating students should be disqualified as clerkship candidates. After talking to Judge Silberman, I began speaking to law students urging that they embrace free speech and cease disruptive protests. I soon realized that Jim was doing the same.

I learned of Jim’s boycott in the press reports following his Kentucky speech. I must admit, I was surprised at his bold stance. But I have known Jim for almost twenty years, having served with him in the Bush Administration. Jim is a serious person, and his idea deserved serious consideration. So, after pondering it for a week, I called him and told him I would join him; he deserved to have someone stand beside him.

The boycott has changed the dynamics. School administrators are now paying attention. The student balance of power has shifted, even if slightly. The student disruptors are in a more defensive posture, and I hope those who embrace free speech feel slightly less afraid.

Are there downsides to the boycott? Of course, but no solution is perfect. Conservative students may choose other schools, but they might have reached the same decision without our involvement. After all, the YLS incident received a fair amount of media coverage and did not shine a positive light on the school.

If someone else has a better idea, I’d love to hear it.

DBL: What would you say to those who accuse you of just grandstanding by weighing in on a topic that will obviously generate a lot of media attention?

JCH: I suppose critics could ask Dean Gerken the same thing: You’re boycotting U.S. News. Aren’t you just grandstanding? I heard a number of comments when I was at Yale last week—folks questioning her motives, suggesting she’s just cancelling U.S. News to get a promotion somewhere.

Personally, I think it’s much more valuable to address the merits of an idea than to lob insults or cast aspersions on character. So I’m happy to assume that she’s doing what she sincerely believes is in the best interests of her institution—and to address her proposal accordingly.

Look, everyone has a choice to make. You can engage people, or you can alienate them. I choose the former.

As you’ve kindly noted, I have a lifelong passion for the quintessential American principles of freedom of speech and equality of opportunity. Students face more intolerance and hatred on campus than ever before. Other efforts to restore freedom of speech have been ineffectual. And now the problem has spread to the rest of the world.

As Americans, what are we going to do about this? Because I refuse to do nothing.

ELB: I always say that a good day for a judge is a day without media coverage. So, it’s a bit jarring to have someone accuse us of seeking it.

I guess I would respond with a question: how important does the issue have to be for federal judges to take a position (outside of a case) that they know might result in media coverage? Jim and I believe that standing up for free speech on campus and speaking out against cancel culture is sufficiently critical that it’s worth the resulting press questions. I’m not sure how that’s grandstanding.

DBL: At the recent Yale event, you said your goal is to stop the cancellation of conservatives at Yale Law and return to what you referred to as “regular order,” presumably an environment of toleration for many different viewpoints. You don’t want the boycott to continue indefinitely.

We have recently seen—in the wake of your boycott announcement, and perhaps not coincidentally—some positive steps for free speech at YLS. What would it take for you to “declare victory” and lift the boycott?

ELB: As I said in my remarks at Yale, “we’ll see.”

The boycott has not yet gone into effect, and Jim and I have said that we would be thrilled if it never does. And it is true that we have seen encouraging changes. We have been told by a number of sources—professors and students—that improvements have been made. But those same sources say a lot of work remains to be done.

I will be watching next semester as controversial speakers come to campus. YLS has a free speech policy. If it is enforced, and if the speakers are allowed to deliver their remarks, Jim and I will revisit the issue. If not, the disrupters will have proved our point.

I cannot imagine that it is in anyone’s best interests for the disruptions to continue. I think the students embarrassed YLS and themselves. I remain hopeful everyone will try to distance themselves from that unfortunate event.

JCH: As I’ve said, I don’t want to cancel Yale. I want Yale to stop cancelling everyone else.

I’ll repeat the same note of hopefulness that I sounded last week. We are starting to see evidence of change. Jonathan Mitchell recently spoke at Yale, where I’m told he was met with rigorous but respectful questions, not disrupted or prevented from speaking. I’m told that Kristen Waggoner will be coming back as well, to address a topic of her choosing. Hopefully that will go smoothly, too.

I’ve also heard from multiple sources that law school deans all across the country are engaging with their students and cautioning them that “we don’t want to become Yale.”

These are all good developments. The goal is not to boycott—it’s to restore freedom of speech and respect for diverse viewpoints, and to stop viewpoint discrimination.

Some students have asked me to expand the boycott—to make clear that we need a diverse faculty. I have to admit that it’s a valid point. If the goal is freedom of speech and debate and nondiscrimination based on viewpoint, it’s hard to imagine how a school delivers on that goal without diversity of viewpoint in the faculty as well as the student body.

Large institutions are always comprised of people with different priorities and motives. I first met Dean Gerken when I judged the Yale moot court years ago. She was gracious and impressive. And of course I already knew she’s a respected scholar—which is why I’ve cited her work in some of my opinions. Judge Branch and I have told her that we want her deanship to be successful. We just think that restoring speech and debate is essential to her success. And we’ve gotten various signals that she strongly agrees with these principles.

I understand that she’s having to manage various dynamics. The cancel-culture crowd is very loud. Defenders of cancel culture are pushing back hard. These are difficult times for law school leaders. But we’ve gotten some indication that what we’re doing may help them steer through this and get us back on track. I like how Lisa put it: The balance of power may be shifting.

DBL: Conservatives at a place like Yale Law have it hard enough as it is. They face real and serious consequences, ranging from social ostracism by their peers and bad grades from their professors, if they articulate unpopular viewpoints. What advice would you give conservatives who are trying to navigate intolerant environments? Isn’t it smarter to just keep quiet, go along with the liberal orthodoxy, and speak their minds after they’ve graduated?

ELB: I certainly don’t fault students for self-censorship these days. Cancel culture can strike any of us.

But there’s a limit to what we should tolerate. While we should certainly be mindful of the feelings of others, we nonetheless are entitled to our beliefs and to express them. The targeting of contrary opinions needs to stop. But how?

As I urged in my remarks, please do not cave to the bullying tactics of the mob. You do not gain anyone’s respect by bending a knee to their demands; they see your concession as weakness. Stand up. Hold firm. It won’t be easy. But I promise you, you are not alone. And your strength will provide inspiration for those more fearful than you. And, at the end of the day, standing up for your principles is the only way you will respect yourself.

JCH: It’s a poignant and profoundly important question, which a student also asked us last week. It’s the same question I keep hearing every time I’m on campus these past few years. My heart goes out to all of them. They’re the reason for the boycott.

These kids deserve better. Much, much better. I love what my wife Allyson told me recently: We’re the opposite of the Greatest Generation. She’s exactly right. Through their bravery, the Greatest Generation made the world a better place for the next generation. We’re the exact opposite. Through our timidity, we’ve made life harder for the next generation.

We don’t teach kids how to tolerate one another, how to agree to disagree. If anything, we’re doing the opposite. Why? Because we’re afraid of them. We’re afraid of being criticized by them. And you see the results of our timidity in every institution in America today.

Students shouldn’t have to deal with this. It should be on us to take care of this. And that’s what Lisa and I are trying to do with the boycott. This should be on us.

Hopefully change is coming. But in the meantime, let me address your question directly. What advice do I have for students today?

Here’s the only advice I’ve been able to come up with. And I fully admit that it’s inadequate.

Let me start with a note of candor. I’m sure it seems awfully smug for life-tenured professors and judges to tell students: Just be brave! Just speak up! I get that the pressure to conform and self-censor is enormous. You’re surrounded by students and professors who are ready to destroy you if you disagree. You don’t want to end your professional lives and careers before they’ve even begun. It’s easier just to say nothing, get good grades, graduate, and get good jobs. I get it. I really do.

So let me just say this. If you can be the first person to speak up, that’s the ideal. It’s okay to be careful. But know that there may be others who share your views, whom you can embolden with your voice. Silence is contagious. But so is courage.

That said, if you can’t be the first voice, at least try to be the second. If someone else stands up first, try to support them. Even if you don’t necessarily agree with them, try to acknowledge that that was hard, that they’ve raised good points that everyone should think about. And if you do agree, say that you do, if you can.

One of my favorite movie speeches comes from the food critic at the end of Ratatouille. As he puts it: “The new needs friends.”

Ed. note: Please note the correction I’ve added to that post. I was referring to Munger Tolles & Olson, whose website quotes an American Lawyer article describing the firm as “progressive—perhaps radically progressive,” and I said I wouldn’t have a problem with Munger dismissing conservative lawyers after making clear that it’s a “progressive” firm. But Munger’s chair, leading trial lawyer Brad Brian, reached out to me to clarify that the comment referred to the firm’s governance structure, diversity, and support for work-life integration; it is not a reference to the politics of its lawyers. As he explained to me, “We are proud that our firm is made up of lawyers with a variety of political perspectives. Diversity has always been a cornerstone of our organization, and we strongly believe that a diverse and inclusive workforce—including respect for differing political viewpoints—allows us to better serve our clients and support one another.”

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; (3) the ability to comment on all posts; and (4) written transcripts of podcast episodes. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

Loved reading this!

This is excellent. Well done in asking the right questions. I deeply respect both Judge Lisa Branch and James Ho. I may not agree with all of their judicial opinions, but I treat that as a point of pride. I take pride in being friends with people from a variety of backgrounds and political perspectives. I learn the most from engaging with a diversity of viewpoints and backgrounds. Free speech as bot judges noted is not something you can apply selectively. It either applies to all or to none. That means yes there will be times when it will lead to decisions one disagrees with, even vehemently. Yet, principles are just that principles. As Judge Ho noted a principle isn't a principle without a cost.