From Federal Judge To... Romance Novelist?

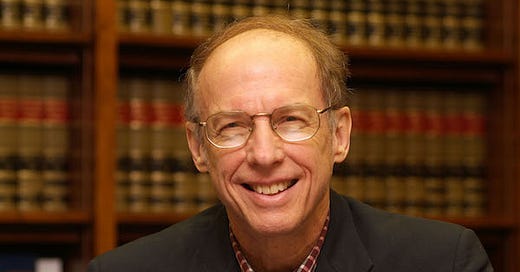

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson—esteemed jurist, former SCOTUS shortlister, feeder judge extraordinaire—opens up about his latest, rather unorthodox project.

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, you can reach me by email at davidlat@substack.com, and you can subscribe by clicking on the button below.

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson is a familiar figure to many readers of Original Jurisdiction. Appointed to the Fourth Circuit by President Ronald Reagan in 1984, Judge Wilkinson is a former Supreme Court shortlister, interviewed by President George W. Bush in 2005 as a possible successor to Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and a current SCOTUS feeder judge, sending many of his clerks into coveted clerkships at the high court. He is the author of six works of non-fiction, most recently All Falling Faiths: Reflections on the Promise and Failure of the 1960s (which he discussed with me back in 2017).

And now Judge Wilkinson is a newly minted… romance novelist?

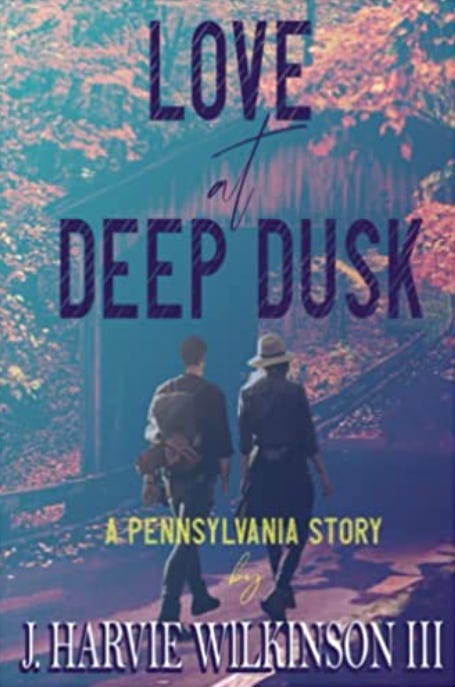

Yes, that’s right: Judge Wilkinson, one of the most distinguished members of the federal judiciary, has written a romance novel, Love at Deep Dusk: A Pennsylvania Story. According to poet Leslie Williams, author of Even the Dark, “Fast-paced, crisply written, and with surprising fateful twists, Love at Deep Dusk will draw you into the rhythms of both small-town life and big-city hustle while provoking lingering questions of home, divided loyalties, and above all, the primacy of love.”

It’s an emotionally affecting book, as well as a page-turner. I finished it in two evenings, staying up late the first night because I couldn’t wait to learn the fate of the protagonists, Leah and John.

Some sources who contacted me about Love at Deep Dusk called it a “romance novel”—“Can you believe Judge Wilkinson has written a romance novel?!?!”—but having read it, I think the better term would be “romantic novel.” It’s a work of literary fiction about love and romance that reflects the themes of the Romantic movement, such as emotion, individualism, and celebration of nature—think more Wuthering Heights, less shirtless Fabio. You can find it on Amazon, not at the supermarket.

But still, for a federal judge to have written an emotion-based, relationship-driven novel, is… highly unusual. So I spoke by phone with Judge Wilkinson to hear more about his foray into fiction. Here’s a (lightly edited and condensed) write-up of our conversation.

DL: First things first: Love at Deep Dusk is a romance novel, but nary a bodice is ripped. I’m not going to lie, Judge—I was kinda hoping for some sex scenes. Why no sex scenes?

JHW: Sex is a powerful motif in the novel, but sometimes it’s more powerful if it’s implicit. I made a deliberate decision not to make it explicit—and I would have been untrue to my characters had I done otherwise. They are very physical human beings, without question, but they would not want the sexual activity between them to be graphically spread out over all the pages.

DL: That makes sense—as a fellow novelist, I totally understand being true to your characters—and it’s consistent with the restraint of your prose as well.

Taking a step back, you’ve written many books over the years, but this is your first work of fiction. Why the pivot?

JHW: My deepest love is unquestionably the law. But I thought a change of pace would be helpful, for several reasons.

For starters, I don’t want my legal writing to become stale. Writing for a general audience helps in this regard: when writing for a general audience, you can’t lapse into jargon, and you have to make things accessible. This change of pace has allowed me to return to the law with renewed energy and vigor.

It's wonderful to write something where I don’t need a second vote. On a court of appeals, you have to convince at least one other judge, and preferably two other judges, that you’re not nuts. With fiction, there’s a freedom in being able to write without looking over your shoulder and wondering if so-and-so is going to concur.

Finally, it’s wonderful to be able to create characters and to create life. For us guys, it might be as close as we’ll come to giving birth. As the writer, you give your characters their names and characteristics, and just like children over time, they act out their own destiny. I enjoy watching that process unfold.

DL: Love at Deep Dusk is not only a novel, but a romantic novel. Your author bio describes you as “a federal judge whose life was touched by so many romantic novels that he set out to write one himself.” How has your life been touched by romantic novels?

JHW: In the course of my reading, romantic novels really stuck with me, and I kept coming back to them. I asked myself: why?

I think it’s because romantic novels touch on what I think is the essence of humanity and both its good and evil aspects. Even in this terribly torn and fractured world, it still seems to me that the most powerful elements in human nature are the ability to love and to forgive, which the romantic novels focus on. They don’t always have happy endings; loving and forgiving are sometimes very hard, sometimes inadvisable. It’s not always easy to love or to forgive—but fiction tells me that maybe, at the end of the day, we have to try.

DL: Are there particular romantic writers or novels that you particularly admire or that touched you powerfully?

JHW: There are so many romantic novels I’ve enjoyed. Some examples are Pride and Prejudice, Ethan Frome, Wuthering Heights, and Our Town—a play rather than a novel, but with a romantic relationship at the heart of it. As for a favorite, I’d say Willa Cather’s My Ántonia. I love its powerful setting, on the Great Plains, and its openness, exploring the freedom the Great Plains gave to young adults to know one another and to roam freely without the restrictions that constrain us today.

You have two people who are childhood or high school sweethearts, and they have different origins and social class and all the rest of it. As life goes on, they drift apart, and when they reunite, their reunion reveals life as it could never be reconstructed.

So you ask yourself: is that a sad ending? Yes, in one sense it’s very sad—what they had can’t be recreated, and it’s gone forever. But in another sense, it’s not sad at all, because the memory of what they had is immortal, and that memory is locked in their hearts forever. Their relationship was perfectly beautiful at the time it existed, and nobody can ever take that away from the people who experienced it. That memory is theirs to keep—and that’s what I think of as the glory and heartache of love.

DL: That makes perfect sense to me in light of how Love at Deep Dusks unfolds. I don’t want to spoil anything for readers, but what you just said perfectly encapsulates your novel.

Shifting gears a bit, other federal judges have written novels—I think of Judges Frederic Block (E.D.N.Y.), Michael Ponsor (D. Mass.), and James Zagel (N.D. Ill.)—but they have written legal thrillers, which makes sense.1 I’m not aware of another judge who has written a romantic novel. How have people responded to this project?

JHW: Some people have said to me, very politely, that it’s “out of character” for me, or that they “didn’t expect” something like this from someone like me. Others have been very supportive. So there’s been a divided reaction.

The people who think it’s “undignified” for a judge to write a romantic novel are right in the sense that judges have to remain dignified. That’s why we put on robes when we hear cases. It’s important not only for us to remain dignified but to keep a certain distance. That’s why the bench is sometimes elevated. I don’t dismiss their concerns. I agree judges need to be dignified and distant—to a degree.

It’s a question of striking a balance. Judges are not marbleized figures; we’re human souls, and we don’t want to become remote and dignified to the extent that we lose contact with our humanity and our communities. So although I have received and fully expect to receive some criticism for this book, I don’t share it. I decided to go ahead because I think a judge should be both distant and human at the same time.

DL: Turning to the novel itself, your protagonist, Leah, has some things in common with you—she’s a lawyer, a spouse, a parent—but she’s also very different. She’s a woman betrayed, with that betrayal at the heart of the novel, and I’m guessing this is alien to your own experience. What was it like to write from Leah’s perspective?

JHW: It was very important for me to have a female protagonist. As a judge, I feel I need to understand experience in its very widest sense. I work at broadening my perspective, and writing this novel was one way of doing that.

The question I ask in this novel is: how does Leah keep it all together? How does she keep her life going? She’s very often both physically and emotionally exhausted. She’s confronted with choices between motherhood and her profession, between her career and her parents, between different places to live. She’s trying to deal with these issues, sometimes by herself and sometimes with the support of friends, but much of it is a solitary struggle. I’ve created a resilient character, but her situation is not easy at all, and it tests her resiliency.

I wanted to explore how people deal with these mega-issues, like death and separation and betrayal, and still keep life with all of its minutiae on track. As a judge, having written this novel, I feel I understand more about people now. It’s a strange journey from fiction to fact and a strange journey from creating characters to dealing with real parties, but writing has helped me understand the struggles that people are experiencing.

DL: Woodson, the small town in Pennsylvania where Love at Deep Dusk is set, is like a character in the book as well. You depict it so skillfully and give readers such a strong feel for it, it’s hard to believe it’s fictional. How did you come up with Woodson?

JHW: It’s a totally fictional town, a composite of different places. It has a firm set of values, just as rural, small-town America has a firm set of values. Those values are under assault, but they’re still there. Patriotism is a value, church is a value, Friday night football is a value. There’s a certain lifestyle in Woodson. There are opportunities for friendship, connection, and community that I’m not sure are present in larger cities.

Whether small towns and their values survive, I’m not sure. Just as Leah is battling her challenges, a small town like Woodson is battling its challenges. Small towns always face this dilemma of young people being raised there but finding the job market not enough to hold them as adults, and so they leave. How do small towns deal with that exodus of adults? Or with plagues like the opioid crisis? Will there be enough different types of business and industry to allow small-town America to thrive? Will this set of small-town values prevail in the end?

We need rural values as part of our national character. We need the best of small-town America as part of who we are—and Woodson has a lot of that. I have great affection for this imaginary town of Woodson and for small towns in general, even as I recognize they’re not free of problems.

DL: You’re a Virginian, yet you set this book in Pennsylvania—the subtitle of the book is “A Pennsylvania Story.” Why Pennsylvania?

JHW: I chose Pennsylvania for a lot of reasons. I used to visit in West Chester with my aunt Lucille, who has passed on, and we used to tell stories to one another. She would sing the glories of Pennsylvania and she said to me one day, “Jay, you must promise me that one day you will write a love story with a Pennsylvania setting.” I said okay, she probably wondered whether I would, and I put the promise away for many years—but at long last it has been fulfilled, and I’m excited about that.

Another reason I chose Pennsylvania is that I was looking for a real contrast between small-town, rural life and big-city, urban life. I found that in the contrast between Woodson, in central Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia. Central Pennsylvania is very interesting—it has beautiful apple country, rich history, wonderful outdoor life, splendid small colleges like Gettysburg and Dickinson—and Philadelphia is a great city.

DL: You have written an immense amount over the years—seven books, almost four decades’ worth of judicial opinions, law review articles, editorials from your time in journalism—but this is your first work of fiction. How would you compare writing fiction with writing non-fiction, especially judicial opinions, and do you enjoy one more than the other?

JHW: I love them both. My first love remains the law, but each has its own values and its own virtues.

I’m a great devotee of classical music. When I think of classical composers like Haydn and Mozart, I think about how so much of the beauty of their work comes from the fact that it takes certain refined forms, like the sonata, and how it follows certain conventions and constraints. That’s the way that law functions, with its allegiance to text, structure, and precedent; it operates within a set of formal rules. There can be flexibility and variation within the rules, but formal structure gives great integrity to the law.

I compare fiction to some of the romantic composers, like Liszt and Strauss. Some of the beauty of their work lies in its extraordinary freedom and open sentiment. They’ve thrown the forms overboard, saying “here it is,” and it all comes gushing out.

When writing fiction, you feel like you’re riding out on a wide-open range—free from statutory text, standards of review, and administrative records. That’s not to say that freedom is a good thing all the time; as a judge, it’s very necessary to be bound by statutes, standards of review, and administrative records. But every now and then, you need to get on your horse and ride across the wide-open range. There’s a beauty to legal writing because of its constraints, but there’s also a beauty to writing without those same constraints.

DL: Many lawyers are aspiring (or frustrated) novelists. For their benefit, can you talk the process of writing Love at Deep Dusk? How long did it take you?

JHW: The novel took me about two and a half to three years to write. I’m a perfectionist by nature and go through multiple drafts, but I remind myself of the old cliché about not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

The thing about writing, whether legal writing or fiction writing, is that it never leaves you alone. A lot of times I’ll close up shop around 5:30 or 6:30 in the afternoon and walk away from my office. But then an hour or two later I think to myself, gosh, I could have done this better, or I want to change this word or this sentence, or redraft the paragraph this way. So even though I thought I was done at 6 or 6:30, there I am at 8:30 or 9, redrafting something because I’m absolutely plagued by the thought that it was wrong or wasn’t what it should be. Sometimes I get up in the middle of the night with a thought and have to write it down before it leaves. The think that makes writing hard is that it’s a 24-hour-a-day process.

DL: How do you balance your legal writing and your fiction writing?

JHW: The legal writing always comes first. My primary dedication is to the law and to my job. I enjoy it, and I want to keep at it. I’m always acutely aware that litigants are before me and waiting on me to provide them with some kind of answer, counting on me to give their work priority and to do my level best. Even if they don’t agree with me, I want them to know that I’ve given them every ounce of energy I have. Fiction is more of a hobby. Some people go into the garage on weekends and do carpentry, but because I would never be any good as a carpenter, I find some odd moments, mostly on the weekends, to write fiction.

DL: Do you have any other novels in the works?

JHW: Ideas take so much time to gestate, and I need to give them time to gestate. I have some ideas and might try to sketch out some scenes, but I’m not hard at work on any particular thing right now, except for my judicial work—which I continue to find exhilarating. I hope to remain on the bench for a good many more years, if health permits, and I’d like to continue to pursue creative writing as a hobby. I’d like to write another novel, but the law always comes first. And I don’t know how many more Saturdays I’ll have to putter around.

DL: Any final thoughts?

JHW: I do hope that readers enjoy my book, since readers are my judge and jury. And I do hope that folks are making the best of their lives and opportunities, contributing to society in very different ways.

I just want to wish everyone well and to say, from the standpoint of someone who’s 77 years old, don’t let a single day go to waste, and don’t let friendships or relationships suffer from neglect. Life has its tough aspects, but it has its joyous aspects too, and I just hope people will make the most of it. Having the chance to live and to love is a blessing, and there are hard patches and real bumps in the road—but at the end of the day, it is a blessing, and I hope everyone will make the most out of it.

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world, as well as the ability to comment on posts. You can reach me by email at davidlat@substack.com with any questions or comments about Original Jurisdiction, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

Judge Block is the author of Race to Judgment, Judge Ponsor is the author of The Hanging Judge and The One-Eyed Judge, and Judge Zagel is the author of Money To Burn. I interviewed Judge Block about his novel here, and I interviewed Judge Ponsor about his novels here and here. (All links to books in this post are Amazon affiliate links.)

All Falling Faiths was a good read, even if it felt a bit navel-gazing to me. I doubt I'll pick up Love at Deep Dusk, it's not quite my genre, but I wish Judge Wilkinson all the best, and I'm glad to see him succeeding in his personal projects!