Trump Judges Are High-Performing ‘Mavericks,’ New Study Claims

Two law professors ranked federal judges based on productivity, influence, and independence—and were surprised by the results.

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking here.

What makes a judge a “superstar” of the federal bench? And how do appointees of former President Donald Trump fare in terms of achieving superstar status?

With Trump running for president anew and four out of nine U.S. Supreme Court justices in their seventies next year, these questions take on added importance. Justices tend to come from the ranks of lower-court superstars—so if Trump returns to the White House and gets to fill a seat (or seats) on the high court, he’d likely elevate one of his prior picks.

More than 20 years ago, New York University law professor Stephen Choi and University of Virginia law professor Mitu Gulati developed a methodology for evaluating judges that focused on three metrics: productivity, influence, and independence.1 They dubbed the judges with the highest overall scores “superstars” (with Judges Richard Posner and Frank Easterbrook of the Seventh Circuit as the top two back in 2003).2

For a new paper, Choi and Gulati applied their framework to the 77 federal appellate judges who were 55 or younger in 2020—43 Trump appointees and 34 non-Trump appointees, roughly a 55-45 percent split. The professors chose this group based on the reasoning that these jurists have the right combination of youth and judicial experience to be considered for the U.S. Supreme Court in the near future. They referred to this judicial cohort as “auditioners,” since some of them appear to be “auditioning” for a spot on the high court.

After reading their paper and finding it intriguing, I interviewed Choi and Gulati earlier this week. I began by asking them why they decided to undertake this project—and why now.

“There was so much hot air in the media about Trump judges being unqualified buffoons,” Gulati explained. “I’m no Trump fan, so I was inclined to believe a lot of it. But Steve and I thought we should look at some data.”3

“There’s always a lot of subjective, anecdotal information out there, like ‘this judge is precise’ or ‘this judge is good,’” Choi added. “We wanted to use objective measures. If you want to say Trump judges are bad or biased or don’t get cited, let’s look at the numbers.”

One possible prediction was that Trump judges would underperform. Based on Trump’s public pronouncements about how “his” judges would act and his own conduct in other spheres, some observers expected him to select judges based on their ability to deliver conservative outcomes or their personal loyalty to him—a “deviation from traditional norms of picking ‘good’ judges,” as explained in the study abstract.

But instead, according to Choi and Gulati, “Trump judges outperform other judges, with the very top rankings of judges predominantly filled by Trump judges.” This was, as Gulati told me, “not what we expected.”

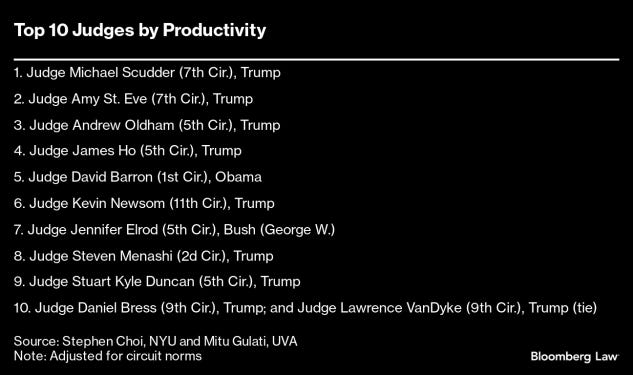

The professors prepared top-10 lists for various metrics. In terms of productivity (adjusted for circuit norms to reflect how much judges on a given circuit tend to publish), Trump appointees took nine out of the top 11 spots (11 because of a tie). Four of the top 11—Judges Andrew Oldham, James Ho, Kevin Newsom, and Stuart Kyle Duncan—have been mentioned by various publications as possible Supreme Court nominees in a second Trump presidency.

For influence, based on citations to a judge’s opinions by federal and state courts outside that judge’s home circuit, nine of the top 10 were Trump judges. Four of the 10—Judges Kevin Newsom, Stuart Kyle Duncan, Britt Grant, and James Ho—have been cited by news outlets as potential high-court picks in a new Trump administration.

Finally, the professors looked at judicial independence—which they also labeled “maverick” status, defined as “a judge who is willing to deviate from other judges, and particularly so those closest to them in terms of political ideology.”

Their most interesting measure of independence was “partisanship” (or lack of), calculated based on how often a judge dissented against a majority opinion written by a colleague appointed by the same political party—e.g., how often a Republican appointee dissented from an opinion written by a fellow Republican appointee.

Of the least partisan judges, seven out of 10 were Trump appointees. Four of the 10—Judges Lawrence VanDyke, Andrew Oldham, James Ho, and David Stras—have been talked about in the media as Supreme Court contenders if Trump regains the White House.4

To Choi, the dominance of Trump judges on the list of most independent jurists came as the biggest surprise: “I thought we would have found more bias—and it pointed out to me the value of having objective data.”

I was surprised as well. When I looked at the complete ranking of judges by partisanship in Choi and Gulati’s paper, the 10 judges who scored the lowest on partisanship—i.e., the judges who are supposedly the most partisan—seemed to me, based on my anecdotal sense of various judges, to be less partisan than Choi and Gulati’s top 10.5

I asked the professors whether perhaps some of the Trump appointees might be scoring as “mavericks” because they are dissenting against fellow Republican appointees in a more conservative direction.6 They acknowledged this as a possibility and identified it as a subject for additional research.

Choi also suggested, however, that our anecdotal senses of judges might reflect cognitive biases, perhaps in favor of more recent cases or cases about hot-button issues that receive extensive news coverage. Their methodology gives equal weight to all cases, whether they concern abortion or ERISA. While Choi and Gulati have received some criticism for this, attempting to weight cases based on a subjective assessment of “importance” runs the risk of introducing the professors’ own biases into the mix.

It might be possible to evaluate the significance of cases based on a more objective measure—for example, the number of amicus briefs filed, which other professors have used to compare the salience of Supreme Court cases. This could be a fruitful follow-up inquiry.

And speaking of avenues for additional research, there are many other ways federal appellate judges could be ranked. One metric that sprang to my mind, given my (perhaps excessive) focus on credentials, would be a “prestige” ranking. It could include how often circuit judges are affirmed or reversed by the Supreme Court, how often they are cited with approval by the high court, and how often they send their own clerks into highly prestigious Supreme Court clerkships—i.e., so-called ”feeder judge” status.

For now, Choi and Gulati should be commended for a valuable contribution to our understanding of federal judges and the federal judiciary. While specific rulings and opinions by individual Trump appointees are open to question and criticism, attempts to paint them with a broad brush as lazy, uninfluential, or partisan will need to engage with this research in a serious and sustained way.

A version of this article originally appeared on Bloomberg Law, part of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc. (800-372-1033), and is reproduced here with permission. The footnotes contain material that did not appear in the Bloomberg Law version of the piece, which you can think of as bonus content for Original Jurisdiction subscribers.

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; (3) transcripts of podcast interviews; and (4) the ability to comment on posts. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.

What led Choi and Gulati to develop this methodology some two decades ago? Gulati gave me more background:

I was living in D.C., teaching at Georgetown, and playing squash at the University Club. There were judges there, they’d talk about who should be on the Supreme Court, and they’d mention things like the contenders’ law schools and clerkships—which struck me as bizarre. By the time someone is under consideration for SCOTUS, we have so much information on how they’ve behaved as judges.

So Steve and I thought to ourselves: why are we ignoring all this highly public, very useful information about judges? That was our motivation. Neither of us did constitutional law or had studied judges before, but we wanted to look at the data.

Choi and Gulati also hoped that tracking and publishing metrics would set up positive incentives for judicial behavior, by encouraging judges to be more productive and to write high-quality, influential opinions that would get widely cited.

The professors received significant criticism for their original paper. For example, Gulati recalled, “Some judges criticized us by saying that we were undermining the dignity of the judiciary by engaging in ‘bean counting’—that we were demeaning the work of judges by reducing it to numbers.”

Gulati acknowledged that there are aspects to the work of judges that can’t be quantified. He argued, however, that the measures that can be quantified might shed light on the others: “In any workplace, some things are visible and some things are not visible. If you’re doing the visible things right—say you show up to meetings on time—that suggests that maybe you’re doing the other things right too. Most things in life I can’t measure, but maybe the things that I can measure will correlate with the things that I can’t.”

Of course, past performance is no guarantee of future results. In Choi and Gulati’s 2003 study, one of the top lower-court judges for independence was then-Judge Samuel Alito of the Third Circuit. As a justice, Alito has been criticized as insufficiently independent of the Republican Party (and rankings by political scientists do show him to be one of the most conservative members of the current Court).

Choi and Gulati also prepared a ranking of judges by their total number of dissents and concurrences, another measure of independence. These were the top 10 by that metric:

Once again, Trump appointees dominate. They made up 55 percent of the total cohort under study, but 80 percent of the most productive judges.

For an anecdotal example, see Judge Ho’s concurrence in the judgment in Jackson Women’s Health Organization v. Dobbs, when that case was before the Fifth Circuit. The majority opinion was by a fellow Republican appointee—Judge Patrick Higginbotham, a Reagan appointee. Judge Ho wrote a concurrence in which he followed Supreme Court precedent but argued that “[n]othing in the text or original understanding of the Constitution establishes a right to an abortion.” The case then went up to SCOTUS, which used it as the vehicle for overruling Roe v. Wade.

Thank you for bringing this study to light. To the extent that the conclusions withstand further scrutiny, should the Federalist Society receive a portion of the credit?

Fabulous reporting, Mr. Lat! This transcends mere legal punditry (which I also enjoy), and constitutes a genuine service to our profession.

I have personal experience only with one of these judges, but I believe I was among the last lawyers to have tried a jury case, which then resulted in a successful appeal, before the Hon. Jennifer Elrod while she was on the bench of the 190th District Court of Harris County (before Dubya nominated her to the Fifth Circuit bench). It was a very garden-variety commercial case, a suit for an accounting arising out of a corporate acquisition. She'd granted partial summary judgment against my client before trial, but I won all the issues submitted to the jury after a very fair trial. I then won a partial reversal of her partial summary judgment, which led to an equitable settlement. When I spoke to her later, congratulating her on her Fifth Circuit nomination, she was extremely gracious about the reversal. And she had other kind words to say about some of my law-blogging she'd come across, which I offer up as a data-point confirming her continuing commitment, on a personal and professional level, to the practicing bar from the bench. I count myself a fan, and I'm entirely unsurprised to see that she scored well in this data-driven analysis.