Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking on the button below. Thanks!

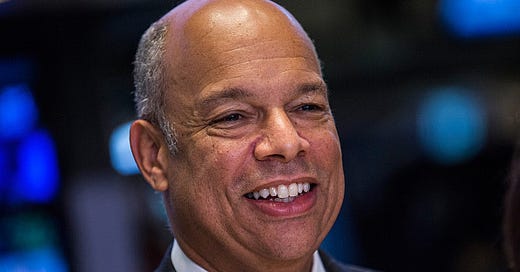

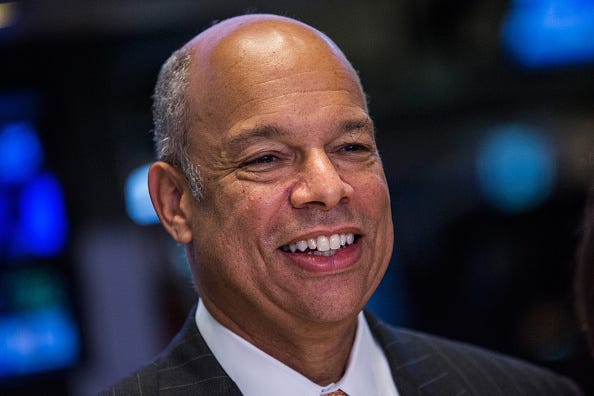

Jeh Johnson, currently co-head of the Cybersecurity and Data Protection practice at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, has had a truly remarkable career in law and public service. Over the past four decades, he has gone back and forth between Paul Weiss, one of the nation’s leading law firms, and the federal government. He has served as an Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York (1989-1991), General Counsel of the Department of the Air Force (1998-2001), General Counsel of the Department of Defense (2009-2012), and finally, Secretary of Homeland Security (2013-2017).

I first met Jeh (pronounced “Jay”) Johnson when he was GC of the Department of Defense (“DoD”) and I profiled him for Above the Law. At the time, he told me he thought it would be his last position in public service. But President Barack Obama had other ideas: in 2013, he asked Johnson to join his Cabinet as Secretary of Homeland Security. From December 2013 until January 2017, Johnson led the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”), a sprawling agency with some 22 components and 230,000 employees, and helped keep the United States safe.

Remembering fondly our 2011 conversation, and eager to hear about his time as a Cabinet official, I reached out to Secretary Johnson late last year to invite him on the podcast. He kindly agreed, and in our conversation last month, we discussed his being an academic “late bloomer”; what he’s most proud of from his time in public life (interestingly enough, not a specific success like the Osama bin Laden operation or the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell); and his advice on mentorship (specifically, how to be a good mentee).

My timing for posting this episode turned out to be excellent: just yesterday, DHS unveiled Secretary Johnson’s official portrait, a tribute to his service to the Department and to the nation. Congratulations to Secretary Johnson on this honor, and thanks to him for his long and dedicated service to our country.

Show Notes:

Jeh Charles Johnson bio, Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP

DHS Unveils Secretary Jeh Johnson Official Portrait, U.S. Department of Homeland Security

An Afternoon With Jeh Johnson, General Counsel of the Defense Department, by David Lat for Above the Law

Prefer reading to listening? For paid subscribers, a transcript of the entire episode appears below.

Sponsored by:

NexFirm helps Biglaw attorneys become founding partners. To learn more about how NexFirm can help you launch your firm, call 212-292-1000 or email careerdevelopment@nexfirm.com.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Original Jurisdiction to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.