This Federal Judge Calls For Giving Prisoners A Second Chance

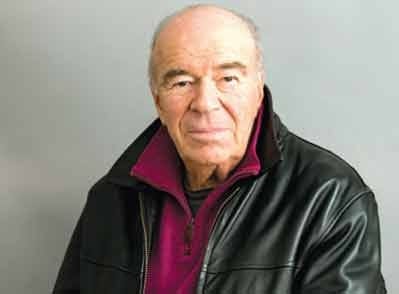

Judge Fred Block, 90, continues to speak out about important issues facing the criminal-justice system.

Welcome to Original Jurisdiction, the latest legal publication by me, David Lat. You can learn more about Original Jurisdiction by reading its About page, and you can email me at davidlat@substack.com. This is a reader-supported publication; you can subscribe by clicking here.

If you ask federal trial judges to name the toughest part of their job, most will cite sentencing. Sentencing a criminal defendant is a weighty decision, affecting years or even decades of that person’s life. And for many years, it was final: a judge couldn’t revisit it, even if there were major changes in the defendant or their circumstances.

That changed in 2018, when Congress passed the First Step Act (FSA)—with overwhelming bipartisan support, including from then-president Donald Trump. Under one of the law’s most important provisions, a federal district judge can reconsider a previously imposed sentence and reduce it—even if that sentence was (and remains) lawful, and even if that sentence was life imprisonment.

What are the requirements for granting this relief, known as “compassionate release”? The critical one is that the judge must find “extraordinary and compelling reasons” for doing so.

And what can constitute “extraordinary and compelling reasons”? It’s currently the subject of extensive litigation in district and circuit courts—which have issued conflicting rulings on multiple issues, making it likely that the U.S. Supreme Court will intervene. (The Court did tackle the FSA last Term in Pulsifer v. United States, but it interpreted a different part of the statute.)1

If and when the justices get involved, I have a reading recommendation for them: A Second Chance: A Federal Judge Decides Who Deserves It. In this engaging and enlightening new book, Judge Frederic Block of the Eastern District of New York presents readers with six defendants who filed motions for compassionate release in his court. He asks us to reflect on whether we would reduce their sentences—then reveals how he ultimately ruled.

His decisions reflect decades of experience. Appointed in 1994 by President Bill Clinton, Judge Block celebrates his 30th anniversary on the bench later this month. And at age 90, he continues to hear cases as a senior judge—with no current plans to hang up his robes entirely.2

“I can’t retire until Glasser does,” Judge Block said—referring to Judge Leo Glasser, who at 100 is the oldest judge currently serving on the federal bench, and whose chambers are just down the hall.3

And Judge Block somehow finds time to write books as well. Last week, I visited him at home—a sunny, art-filled apartment in Greenwich Village, where he has lived for almost three decades—and interviewed him about A Second Chance. It’s his fourth book—or his fourth to be published, at least, since he has two completed manuscripts that he’s trying to publish, plus another that’s already 100 pages.

He started writing A Second Chance in July 2023, at the home in Greece where he and his wife Betsy spend the summers. By September, the book was more or less done—because, the judge told me, “At my age, I have to write fast.”4

I asked Judge Block what inspired him to tackle this topic.

“The First Step Act is probably the most significant piece of sentencing reform I’ve ever experienced,” he told me. “It really changed the sentencing landscape in the United States. In deciding motions for compassionate release under the act, I came across all of these fascinating stories—which gave me the idea for the book.”

The cases he shares in A Second Chance make for compelling reading. He begins with that of Justin Volpe, the former New York City police officer notorious for brutalizing Abner Louima, a wrongfully arrested Black man, in 1997. Judge Block then describes the cases of a drug dealer implicated in a murder, a computer programmer who accessed child pornography, and three Mafia defendants. In the end, the judge reduced the sentences of two of the six defendants.5

And he continues to receive motions for compassionate relief—as do judges across the country. As of January 2024, 4,680 inmates have been released by judges since the First Step Act took effect. Prior to the FSA, only the Federal Bureau of Prisons had the power to grant compassionate release—which it rarely exercised, granting relief to an average of only two-dozen defendants per year.

But as discussed in A Second Chance, and as Judge Block mentioned again when we spoke, federal prisoners constitute only about 10 percent of the total prison population in the United States. The remaining 90 percent are in state prisons and local jails. Judge Block believes that they too should be eligible for compassionate release—and describes his book as “my clarion call to all the states to follow Congress’s lead and enact their own First Step acts.”

I asked him: how likely is it that states will act? Proponents of criminal justice reform appear to have lost ground to the “tough on crime” camp. Donald Trump, who used to brag about signing the First Step Act, no longer talks about it—and instead claims on the campaign trail that he is “the law and order candidate.”

“I’m not overly optimistic,” Judge Block admitted. He suggested that in the current political environment, some politicians fear the electoral consequences of being seen as soft on crime.

But he noted that at least some states are considering reforms—including New York, where Senator Julia Salazar (D-N.Y.) has sponsored the Second Look Act. And he said that even if the odds are against him, he won’t stop “urging people to think about the issues our justice system faces—and the number-one issue, in my view, is mass incarceration.”

“After 30 years on the bench, I have the confidence and security to talk about the things that bother me,” Judge Block said. “So I’ve taken this opportunity to speak my piece.”

Dissenting in Pulsifer, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote that the First Step Act “may be ‘the most significant criminal justice reform bill in a generation’” (citing an amicus brief filed by Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill.)).

Judge Block has been on senior status for almost two decades, since September 2005—and described it to me as “the best judgeship you can have, because you have all this control.” Senior judges can decide how heavy a caseload they would like, and they can opt out of certain categories of cases they prefer not to hear (e.g., cases filed by pro se litigants, which Judge Block no longer handles). As for when he might step down from the bench completely, Judge Block told me that he takes it “year by year”—and as long as his health continues to hold up, he plans to keep on going.

For a deeper dive into Judge Block’s long and interesting career, check out our podcast conversation.

Judge Glasser was appointed in 1981 by President Ronald Reagan and took senior status in 1993. Judge Block referred to Judge Glasser, who still comes into chambers four days a week, as “an inspiration.”

Judge Block’s publisher, The New Press—where he worked with Diane Wachtell, editor of a landmark book about criminal justice, Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness—also moved swiftly, in terms of taking A Second Chance to press. With an official publication date of this coming Tuesday, September 17, it arrives in time for the 2024 election—and Judge Block hopes it can contribute to a national discussion about criminal-justice reform.

In the Second Circuit, whose case law controls Judge Block’s decisions, two key precedents are United States v. Brooker and United States v. Fernandez. According to Judge Block, Judge Guido Calabresi’s opinion in Brooker “gives broad discretion to sentencing judges” when ruling on FSA motions, while Judge Robert Sack’s opinion in Fernandez “walks Brooker back a little.”

The Fernandez court held that “[c]hallenges to the validity of a conviction—including potential-innocence claims—cannot qualify as ‘extraordinary and compelling reasons’” under the First Step Act. It also rejected the defendant’s argument in that case for compassionate release based on sentencing disparity—but left room for future defendants to assert such claims. As noted by Professor Doug Berman, Fernandez’s “discussion of sentencing disparity as a legal basis for possible sentence reduction is quite nuanced, and it includes a lengthy footnote starting with this sentence: ‘We cannot foreclose the possibility that significant sentencing disparities, even between a defendant who went to trial and a co-defendant who pleaded guilty and cooperated, might, in some unusual circumstances, warrant a finding of ‘extraordinary and compelling’ reasons to grant a sentence reduction.’”

What matters most to Judge Block when considering motions for compassionate release? To him, the most important factor is rehabilitation. Even though rehabilitation standing alone cannot warrant a grant of compassionate release, it can be considered along with other factors, allowing a judge “to do what is fair and just under the circumstances.”

He added that rehabilitation is especially persuasive for defendants who were initially sentenced to life imprisonment: “When you have someone in prison who was told that they were going to be there for life—with no expectation that this statute would be passed, expecting instead that they would die behind bars—and that person nevertheless turned their life around, they should be considered for a second chance.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Bloomberg Law, part of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc. (800-372-1033), and is reproduced here with permission. The footnotes contain material that did not appear in the Bloomberg Law version of the piece, which you can think of as bonus content for Original Jurisdiction subscribers.

Thanks for reading Original Jurisdiction, and thanks to my paid subscribers for making this publication possible. Subscribers get (1) access to Judicial Notice, my time-saving weekly roundup of the most notable news in the legal world; (2) additional stories reserved for paid subscribers; (3) transcripts of podcast interviews; and (4) the ability to comment on posts. You can email me at davidlat@substack.com with questions or comments, and you can share this post or subscribe using the buttons below.